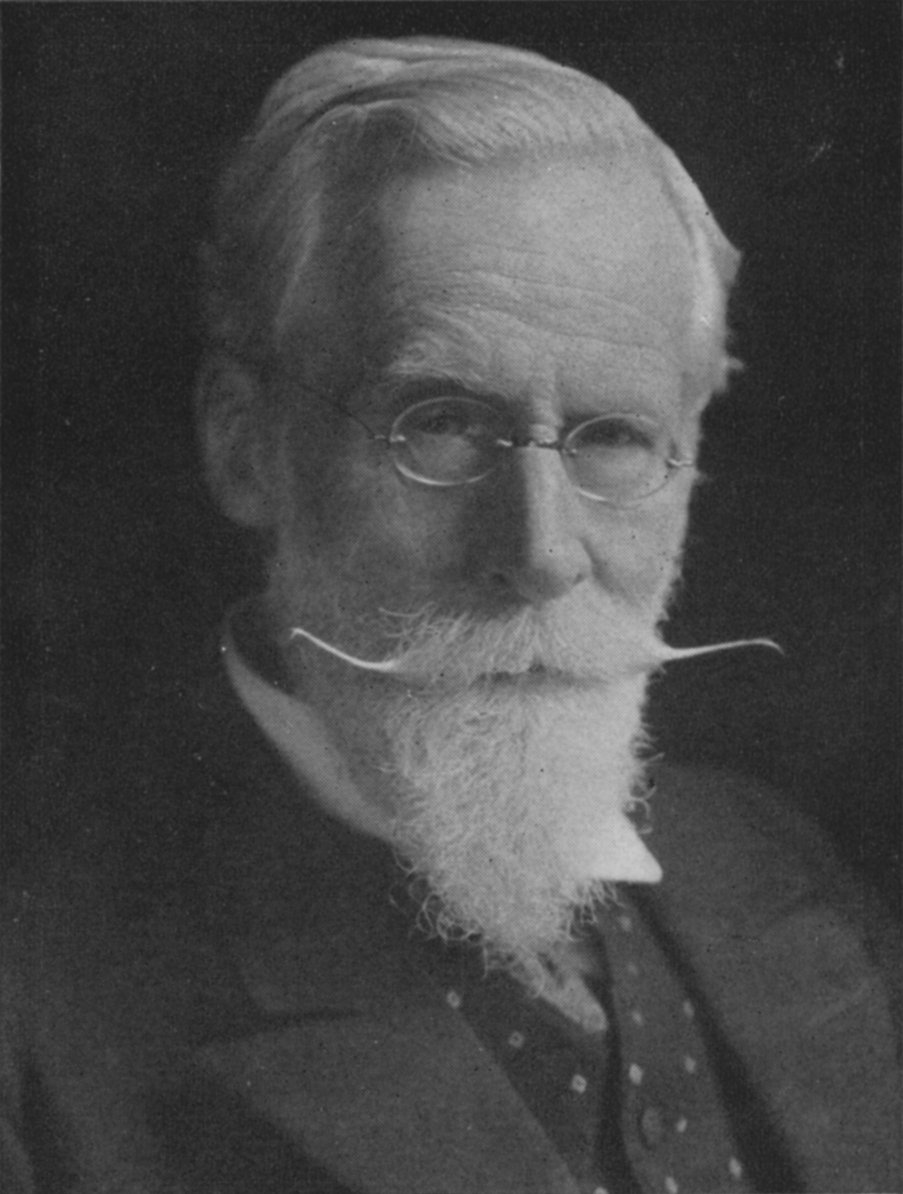

Sir William Crookes, OM, FRS (17 June 1832 - 4 April 1919)

Borderland Visionary:

The Life of Sir

William Crookes

by Gerry Vassilatos

IN the pantheon of our qualitative science there stand a grand assembly of highly venerated persons, the mere mention of whose names is sufficient to evoke inexpressible sentiments. Some of these have been justly venerated to a station which is not inordinate, being of such grand stature in their achievements that to deny them due homage would be unjust. We note that a few of these distinguished ones so deeply touched each their generation, that whole epochs became intimately associated with their names alone. How beautiful and fitting that we find it often quite impossible to mention certain scientific periods without first recalling them, name by name. These are the doorkeepers of an epoch, who names must first be acknowledged, evoked so to speak, before being permitted entry into their realms of knowledge. No greater earthly glory can be acquired by mortals.

ROYAL

The Royal Society had gathered to hear a lecture by one of the most eminent members who had ever blessed their halls. After having been announced by the president of the Society, the principle speaker walked to the large proscenium area, took his place behind the wide demonstration table and began to speak in a fervent, ringing voice. He was elderly, formally dressed in a black waistcoat of a former time. The loose black evening cravat wrapped the high white collar, and neatly, framed the now radiant face.

Bright and cherubic, in glittering spectacles, the guest looked down for a brief moment. It was as if he lingered in some wonderful clear peace, awaiting an inner impulse to speak. His trimmed silvery moustache and the pointed silvery beard lent an otherworldly air, and as he looked up again all eyes came to rest upon the curious elfin figure. This was not the first time that the assembled members of the Royal Society had seen the wonderful Sir William Crookes. No one present in that assembly could have long remained ignorant of the man standing before them. Sir William and his mysterious investigations into Radiant Matter had captivated the greatest minds of his time. And while most believed that the aetheric implications of his work had been explained away, there remained a lingering suspicion among a dwindling membership that he had eluded them all with a far deeper secret.

“When I was asked a month or two ago to illustrate in this theatre some of my recent researches on high vacua, I exclaimed how is it possible to bring such a subject worthily before a Royal Institution audience when none of the experiments can be seen more than a few feet off?” Two former decades had passed since his first demonstrations on Radiant Matter were given. It might as well now have been a former age. So rapidly had the scientific movement taken the industrial world, that the famed Crookes Tube seemed to be an antiquated and elementary device. But perhaps then, few had actually comprehended the full meaning of that simple “antique.”

He once believed that he had been careful about elucidating these matters. He also believed that his original dissertation, presented in 1879, had been clear and forthright to the illustrious Society. There was no reason for him to doubt his proficiency in the lecture hall. How far can facts be twisted, taken from fact and distorted into rumors? But over the long decades, he sadly observed a peculiar reaction which repeatedly worked to dispel any new advancements in thought. There were those Society members who, after both having seen his classic demonstrations, somehow failed to sustain the precise message which had been delivered to them. This strange principle maintained an arrested consciousness in the scientific ranks of the Society, rendering them incapable of philosophical progress. And without first appreciation for philosophical principles, there would never be true scientific progress.

“Like a traveler exploring some distant country, the wonders of which have hitherto been known through reports and rumors of a vague and distorted character, so for years I have been occupied in pushing an enquiry into a territory of natural knowledge which offers almost virgin soil to the scientific man”. The majority were now unable to hear the simplest ofhis statements without somehow automatically “reinterpreting” his ideas. This automatic process consistently obscured topics which opened to the more vitalistic aspects of natural lore. This degenerative process obscured the real impost of his work, that which literally claimed to point a way toward a vision of deeper dimensions. But in them, he perceived a growing ignorance, which was not so much a darkness of intellectual resource, but a darkness of intellectual use.

The amount of factual information had increased beyond the ability of science to remember all that had been observed. But the manner in which these facts were reorganized and reinterpreted which deeply distressed Sir William. “Are we to investigate nothing till we know it to be possible?” In his estimation, science was on the verge of an important divergence, one which limited scope by a stringent doctrine. It would thus become polarized, on the one hand opening up to new awareness, yet on the other resisting change.

“It is not reason which convinces a man, unless a fact is repeated so frequently that the impression becomes like a habit of mind.” What he [12] now recognized was far worse than scientific agnosticism. Having miscarried the vision which had been faithfully delivered to them, the younger generation of “scientifics” had chosen a selective number of facts, and certainly not the philosophy. It was rather like being given a lovely rose bush . . . cutting off a few roses, and then killing the shrub! The eradication ofall things pre-modem seemed more important to the young scientific revolutionaries than the reverence of learning, of knowledge, and of a deeper vision.

But this revulsion of all things pre-modem manifested an unmistakable tendency to repulse and repudiate themes which were Vitalistic. And the lifelong theme of Sir William Crookes was a Vitalistic theme.

“With all my senses alert and ready to convey information, believing as I do that we have by no means exhausted all knowledge or fathomed the depths of all physical forces.” So here stood the very personification of that antique worldview, and the Hall was never more divided in their opinion of his presence near the proscenium. Having well comprehended the present dilemma, Sir William fully intended to baffle the minds of his younger antagonists. “The consciousness of my senses, both of touch and sight . . . and these having corroborated by the senses of all present… are not lying witness when they testify against my preconceptions.”

Many had already critiqued his past works in the scholarly journals, mocking his “simplistic” views. But he was not concerned that his work was being critiqued, so much as that the Victorian approach to science was being critiqued. There was already an established background of biased thought, a progressive epidemic of erroneous doctrine. “If a new fact seems to oppose what is called a’law of Nature,’ it does not prove the asserted fact to be false, but only that we have not yet ascertained the laws of Nature. or not learned them correctly. And if you find a fact, then avow it fearlessly, as by the everlasting law of honor you are bound to do so.”

He fully intended on thwarting the proliferation of this doctrine by throwing a few simple facts into the group mind. Any convincing polemic in the Victorian tradition would stand to confront the new and alienating quantitative science. The well-organized machinery might be disrupted by an experiential form of sabotage. He would attack their dead view of the world by giving them such an irrefutable experience of his realm so as to haunt the Hall and its annals for a century if necessary.

GEMS

When his work with electrostatic discharges in vacuum was first brought forth, it was immediately wrangled into a theory of particles and quanta. For Sir William, his experiments with ultravacuum began as an extension of experiments performed by Baron von Reichenbach. His intention was to test those early experiments by which the Baron discovered a luminous emanation exuded by magnets in vacuum. Sir William’s thought was to extend this principle to an exploration of the electrostatic field in vacuum. Would the electrostatic field reveal a new world of Light when the vacuum was very high? But that noble name of Reichenbach was forgotten by his colleagues, buried along with Mesmer and Galvani. The work of each of these legends, in their study of vital force, had somehow managed to offend the intellectuals. Their scientific approach had no place for vital energies.

“New forces must be found, or mankind must remain sadly ignorant of the mysteries of Nature. We are unacquainted with a sufficient number of forces to do the work of Universe.” The only recognized forces consisted of gravitation, magnetism, electrostatics, and the new nuclear force. Theories which might as much as intimate the existence of soul, spirit, or vital force were very much despised. Sir William had long championed the notion that the qualities of matter were not sourced in their “atomic focal points.”

In these experiments with ultravacuum tubes, Sir William had consistently observed that matter was possessed of a whole and continuous nature, bearing qualities which emerged into our world from a “fourth state.” The process of allowing matter to expand in an ultravacuum seemed to reveal these qualities in the complete absence of inertia. Had he found an experimental means for proving the existence of Platonic Solids? His classic work with vacuum discharges was concerned with the deep mysteries of space, of a peculiar black radiance, of radiant matter, a fourth state, of force, and of light. In their ultimate implications, Sir William intended to instruct on certain aspects of the human aura, the world of ectoplasm… the world of matter in the fourth state, of intimations concerning the luminiferous aether, and of consciousness.

Tonight he hoped to again clarify and disentangle the singular distinctions of his original thesis from all the confusion which had transpired in the intervening decades. Those younger and more discourteous appointees had already been taught to reject Vitalism without so much as a breath. The rejection was becoming automatic, easy. It was unbefitting for scientifics to refuse skeptical examination before repudiation. For them, the gentlemanly figure was merely an silvery antiquated curiosity who was satisfied to delve in dubious and unscientific realms of research. Worse. For some, the legendary name of Sir William Crookes had already been “tainted” because of his willingness to explore psychokinesis and other paranormal forces, as did Baron von Reichenbach before him. Many did not therefore wish to hear Sir William speak at all. ”

But he had longtime experience of the audacious accusations levelled against him for this research on the paranormal. Sir William had already prepared himself against this prejudicial atmosphere, and fully intended on dispelling the many intolerant presumptions in the audience. And yet he managed an unearthly jolliness! He was not vindictive, but was rather soft in approach. He would summon all the magic in his delightful devices, his arsenal of marvels, to reach these darkened minds.

In addressing the Royal Society he hoped to haunt the whole world of Science with a deeper view of natural reality. A vitalistic view. Toward this end, he would use one weapon: sensation. Direct, tactile, and irrefutable. Sensation would work with him, achieving some new reawakening.

“The kindness of your late secretary, Mr. Spottiswoode, placed at my disposal his magnificent induction coil, not only for this lecture, but for some weeks past in my own laboratory; thus enabling me to prepare apparatus and vacuum tubes on a scale so large as to relieve me of all anxiety so far as the experimental illustrations are concerned.” His face shone, a childlike willingness to share what he had learned. This brotherly nature and merry mood was a birthright which he inherited from living in a large extended family. He was fun to watch! As he began, a mercurial levity filled the hall, and the mere mention of each supportive discovery in his theme filled the many diverse listeners with an enthralled sense of mystery. While he spoke, the august assembly was silent.

“Anomalies may be regarded as the fingerposts along the high road [13] of research, pointing to the byways which lead to further discoveries. Now these residual phenomena, these very anomalies, may become the guides to new and important revelations.” He was always sensitive to atmospheres and vibrations. In surveying the Hall, he was now also sure that his audience had lost all awareness of his principle reasons for conducting those first experiments in high vacuum electrical discharges. But he was energized by the prospect and, having brought forth his now classic tubes from their dusty old glass cases, was fully ready to command the scene. Surrounded by his now-famous collection of large vacuum globes and specially designed Ruhmkorff Coils, his eyes twinkled with delight.

His was a voice which had the power to convince and thrill. “In the course of my research, anomalies have sprung up in every direction. I have felt like a traveler, navigating some mighty river in an unexplored continent . . . and promising rich rewards of discovery for the explorer who shall trace them to their source”. He was a model of the romantic and heroic Epoch, enabled by some wonderful inner force to formulate concepts which had previously occurred to no one. It was the manner in which his mind managed to “ask the right questions,” “see the right effects,” and “make the right connections” that set him apart frommost others.

“In Science, every law, every generalization, however well established, must constantly be submitted to the ordeal of a comparison with newly discovered phenomena . . . and a theory may be pronounced triumphant when it is found to harmonize with, and to account for facts which, when it was propounded, were still unrecognized or unexplained.”

Though his manner was cordial and cheerful, he did not lack in the disciplines required by his profession. Of the scientific professional he said, “[H]aving once satisfied himself that he is on the track of a new truth, that single object should animate him to pursue it…without regarding whether the facts which occur before his eyes are naturally possible or impossible.” Indeed, in this theme, he penetrated avenues of contemplation which were positively astounding. His was a vibrant and inspiring mind which was exceptionally creative on a great many issues of natural science.

“The little bye-lanes often lead to the most valuable results. After a while the facts group themselves together and best tell their own tale.” This rare and innate forte permitted his subtle but decisive ability to shock and surprise his students. But he laughed and chuckled as he spoke. Was this a scientist . . . or a magician? For those who loved Sir William Crookes, this was quite an event. Here was a reasonable lesson on a field of inquiry having potentially unreasonable directions.

But the audience was not filled with his admirers, of this he was well aware. Some had already committed the most unforgivable and ungentlemanly acts of cowardice. Having attacked his investigations in the scholarly journals, there were those who attended in order to obtain more evidence against his methods and themes. Those persons sat in his audience. But he had no animosity toward them. None was left amid the joy of love, the joy of illuminated wonder.

“Dr. De La Rue, who occupied the chair, good-naturedly challenged me to substantiate my statement that there is such a thing as a fourth, or ultragaseous state of matter. I had no time then to enter fully into the subject, but as I find that many other scientific men are in doubt, I will now endeavor to substantiate my position.” The lecturer surveyed the hall. Sir William was an exceptional master of the dramatic, exercising a distinct and unique flair by which had also become renown. Besides presenting a strictly scientific thesis, he thoroughly exploited the more theatrical aspects of the lecture hall.

Each aspect was part of his method, a method designed to stimulate an epiphany in each hearer. Metaphorwas often more valuable to his method than mathematics. He knew how to move the inflexible pride. Drama and other emotionally provocative movements were always successful in stimulating the prelude to learning, to true change. Without drama, there could be no impression in the icy world of the Royal Society. Radiance and color, darkness and Light. The prelude to Light was darkness. But before light could penetrate the mind, before it became a beauteous contrast to isolating emptiness, there had to be an immersion in darkness. The room was therefore necessarily darkened for several moments. When all eyes were now accustomed to the dark, his voice rang out quite suddenly. “One of the most noteworthy properties of Radiant Matter is its power of exciting phosphorescence.” In an instant, out of the deep darkness, a green light flickered momentarily in midst of a large glass globe.

His beaming face was semitransparent as the pure green rays flooded the Hall. “My earlier experiments were carried on by the aid of a strange natural phosphorescence which glass takes up when it is under the influence of the radiant discharge; but many other substances possess this phosphorescent power in a still higher degree than glass.” The current was applied to another globe, one which housed a large mineral crystal. As it sprang into a blue brilliance, the room grew hushed once more. The color filled the entire room. “When this sulphide of calcium is exposed to the discharge in a good vacuum, it will phosphoresce for hours.” Withdrawing the electrical current, the stone continued glowing as brilliantly as if continually stimulated by an unknown radiant source.

“Without exception, the diamond is the most sensitive substance I have yet met for ready and brilliant phosphorescence. ” The diamond, mounted on a post within the large globe, was now glowing in a vivid green light. The sight moved the entire room. Everyone leaned forward to see, to gain some sense and feel of the phenomenon. Sir William smiled with glee! There! The vibrancy of that wonderful diamond light was fast melting away all academic resistance, all the critical effrontery, all the callous aristocratic pretense. That diamond light dissolved every personal wall, releasing the child in each member once again. The most acrid of academes remained positively entranced by the glow of his lamps.

Their vitality returned as fresh as springtime. It was as if many of them were awakened from a deep sleep of the mind. And here was his brilliant, wordless theme at once unfolding! His commentary was just as resplendent, deeper in fact than the light which now issued from the vacuum tube. His joyous voice continued. “Next to the diamond, the ruby is one of the most remarkable stones for phosphorescing.” Assistants quietly switched off electrical power from the large Ruhmkorff Coil in the center of the demonstration table. Electrical connection was established with a second large globe, an elongated ovoid.

“Nothing can be more beautiful than the effect presented by a mass of rough rubies when glowing in a vacuum.” As the current was silently applied, the entire large ovoid globe became a dazzling red light. “They shine as if they were red-hot.” The color permeated the room. “In this tube of rubies, there are stones of all colors… the deeper red and the pale pink… but under the impact of Radiant Matter they all phosphoresce with the same color.”

VERMILION

Rubies. Collections of rubies. He looked out into the crowd from his place behind the table. All faces were clearly seen in that red radiance. Each reflected back varying degrees of that pure and deep vermilion light. As he observed this remarkable effect on the face of his audience, he thought aloud. “It scarcely matters what color the ruby is to begin with …under the impact of Radiant Matter, they all phosphoresce.” Some managed to derive from that phrase deep meaning. There were those who long lingered on that phrase, for it taught a multitude of lessons quite all at once. This was the remarkable manner and style of Sir William. He always managed to speak on several simultaneous levels. On one level, there were the scientific revelations. On another, the social implications. On yet another, the personal revelations. What was it about his personality or subject matter which permitted this astounding juncture of consciousness?

The deep light of his rubies flared into a deeper and more brilliant light. The wonder of his life was not unlike these wonderful glowing tubes. He had come out of the darkness, out of a peculiar class vacuum, was touched by some thrilling and inscrutable energy, and became suddenly radiant! And here he was, as so many previous appointments had invited, standing and lecturing to the Royal Society. How had it happened, that he of all people was granted such favor as to be elevated to his present station?

Between the thoughts which were now flooding the hall, between the lines of his lecture, between the strokes of a second hand, he quietly turned his gaze to the radiant rubies for another look. Just then, just as he paused to gaze into the deep red light of his ruby tube before opening the switch, Sir William looked into another world. A window suddenly opened to him, and he looked in. The innocence of his childhood was always close to the surface. He recalled how his mother would called to him from the lower floors of childhood’s home. He had been wondering at the morning sunlight far too long, gazing out at an upper windowpane. The other younger children had already surrounded the kitchen table and were awaiting his presence.

Seated and ready for morning prayers, breakfast, kindly admonitions, and school, the family waited for the eldest son to take his place. As William quickly arrived, it seemed to him that the entire household was full of light. Light was everywhere, or was it just an afterimage? Seated near his father, and casting his gaze all around him, he saw the light glowing in his little brothers and sisters. No, he was sure. This was no disappointing afterimage. This was the light of life, and it merged with the sunshine in a most remarkable way.

William loved to hear his father’s many accounts. His father was something of a wonder, a life filled with a hundred episodes. Those were the days when families sat at table together, respectfully hearing the tales and admonitions of their elders. Each of his father’s stories had their distinctly miraculous tone. The chapters in his life read less than that of a poor tailor from the country, and more like the chronicle of a minor prophet. His father was born of poor parents, a misfortune at any time in English history. In England, being born in poverty, meant that one died in poverty. There were no informal means for achieving some kind of social mobility in the rigid caste system. No mobility whatsoever, except for the occasional “accidents.” And the elder Joseph Crookes certainly attested to these, although he never believed in the “accident” of a divine blessing.

Out of poverty, in some inexplicable manner, his father was fortunately apprenticed to a master tailor who lived in his township. In time, Mr. Crookes also successfully acquired the title of master tailor. Yet Rubies. Collections of rubies. He looked out into the crowd from his place behind the table. All faces were clearly seen in that red radiance. Each reflected back varying degrees of that pure and deep vermilion light. As he observed this remarkable effect on the face of his audience, he thought aloud. “It scarcely matters what color the ruby is to begin with …under the impact of Radiant Matter, they all phosphoresce.” Some managed to derive from that phrase deep meaning.

There were those who long lingered on that phrase, for it taught a multitude of lessons quite all at once. This was the remarkable manner and style of Sir William. He always managed to speak on several simultaneous levels. On one level, there were the scientific revelations. On another, the social implications. On yet another, the personal revelations. What was it about his personality or subject matter which permitted this astounding juncture of consciousness?

The deep light of his rubies flared into a deeper and more brilliant light. The wonder of his life was not unlike these wonderful glowing tubes. He had come out of the darkness, out of a peculiar class vacuum, was touched by some thrilling and inscrutable energy, and became suddenly radiant! And here he was, as so many previous appointments had invited, standing and lecturing to the Royal Society. How had it happened, that he of all people was granted such favor as to be elevated to his present station?

Between the thoughts which were now flooding the hall, between the lines of his lecture, between the strokes of a second hand, he quietly turned his gaze to the radiant rubies for another look. Just then, just as he paused to gaze into the deep red light of his ruby tube before opening the switch, Sir William looked into another world. A window suddenly opened to him, and he looked in. The innocence of his childhood was always close to the surface. He recalled how his mother would called to him from the lower floors of childhood’s home. He had been wondering at the morning sunlight far too long, gazing out at an upper windowpane. The other younger children had already surrounded the kitchen table and were awaiting his presence.

Seated and ready for morning prayers, breakfast, kindly admonitions, and school, the family waited for the eldest son to take his place. As William quickly arrived, it seemed to him that the entire household was full of light. Light was everywhere, or was it just an afterimage? Seated near his father, and casting his gaze all around him, he saw the light glowing in his little brothers and sisters. No, he was sure. This was no disappointing afterimage. This was the light of life, and it merged with the sunshine in a most remarkable way.

William loved to hear his father’s many accounts. His father was something of a wonder, a life filled with a hundred episodes. Those were the days when families sat at table together, respectfully hearing the tales and admonitions of their elders. Each of his father’s stories had their distinctly miraculous tone. The chapters in his life read less than that of a poor tailor from the country, and more like the chronicle of a minor prophet. His father was born of poor parents, a misfortune at any time in English history. In England, being born in poverty, meant that one died in poverty. There were no informal means for achieving some kind of social mobility in the rigid caste system. No mobility whatsoever, except for the occasional “accidents.” And the elder Joseph Crookes certainly attested to these, although he never believed in the “accident” of a divine blessing.

Out of poverty, in some inexplicable manner, his father was fortunately apprenticed to a master tailor who lived in his township. In time, Mr. Crookes also successfully acquired the title of master tailor. Yet unemployed, the hope of rising out of his impoverished station seemed dim. It was shortly after this sad realization that the smallest light of an opportunity twinkled for him in the distance. The children always liked this part of the story. Father repeatedly told how he had come to London, poor and humble, in hopes of earning the smallest living. Used to poverty, any work would have satisfied him. “Crookes” was an unlikely name for anyone to trust. They all laughed. But this master tailor was no twisted branch, no prodigal son. Hard work, perseverance, and prayerful diligence prevailed. Employed in a small tailor shoppe, Mr. Crookes began his routine with great thanks. He was fortunate to have secured such a position.

Soon, he was married to his second wife, Mary Scott. William, their eldest son, was born on June 17,183 2. Then the magic in their lives grew, for the elder Mr. Crookes suddenly found himself the focus of a monetary whirlwind. It was one which did not cease its spinning magic until a veritable trail of silver flooded the Crookes family purse. The small twinkling light which had brought him to London became quite a brilliant stream. From town to city. From poverty to riches. William never tired of this wonderful story, this family history. Over and over again, he turned the episodes in his heart. Once their message reached his mind, he saw them as something of a sure hope. If his father could have escaped poverty against those impossible odds, then he might also further the fortune of his life. If only the same blessings were on him, who knew where the paths would lead?

Without that inscrutable blessing, so obviously at work in his father’s life, William knew that he might never have had opportunity to study natural science. And natural science was what his heart loved best. He was thankful, grateful for all those about him. But the clock struck the hour, and the family parted until dinner once again. William was off to a day of lectures and laboratory exercises at the Royal College of Chemistry. His father’s kind eyes spoke in silent approval. William was not going to be a tailor. Just as well, he was exercising a new kind of apprenticeship. This was a new world, was it not? Was anything impossible?

William would try to do as his father had done. This sweet and golden image of sunny early days never faded in his mind. Its treasure merely withdrew at times, slipping beneath a red setting sun. The sea softly rippled with other luminous thoughts. Red luminous thoughts. The red radiance of his tubes reached their crescendo, flared more brilliantly, and Sir William felt the Lecture Hall around him. He withdrew the power, and watched the rubies sustain their individual colorations. Their afterglow was a special effect which few ever appreciated. He noted that only a few continued to radiate light. Looking out into his audience, he saw the same effect. Some faces shone more brilliantly than others. Some would not glow as brightly. Yet others would show themselves incapable of reflecting any light at all.

This reverie, known to him alone, was far too touching. He felt much humbled. How ordinary he was in comparison with most of these persons who were seated before him! He was not the son of upperclass breeding. He bore no aristocratic emblem. He had no ancient lineage to claim extraordinary right. But not one of them had the fire of light within. Not one seemed to draw radiance from the light. Yet here he stood, the son of a once-poverty stricken tailor. Here… among the rubies!

SPECTRUM

“The spectrum of red light emitted by these varieties is the same as [15] described by Becquerel twenty years ago. There is one intense red line . . . having a wavelength of about 6895…and a few fainter lines beyond it, but they are so faint in comparison with this red line that they maybe neglected.” Indeed, only the brightest colors are noticed and prized. He recalled the day he was entered into The Royal College of Chemistry in London. It marked the episode which proved to him that blessings do not fade.

His was a biography which seemed in every aspect identical to the good fortune of another young man. Years before, the young Michael Faraday was elevated to eminence. Though a bookbinder’s apprentice, it was the exuberant love of all things scientific which first attracted Faraday to audit lectures at the Royal College. Through a similar series of encounters, Faraday met the great Humphrey Davy, and became his personal assistant.

When William Crookes was asked to be August Wilhelm von Hoffmann’s own personal assistant, a definite turning point was reached. It was one which forever sealed his fortune. William so impressed the master chemist with his innate and intuitive laboratory skills, that he was soon invited to attend lectures at the Royal Institution. There, young William heard presentations by the most eminent scientific explorers of his day, a profusion of diverse topics. The meetings introduced him to an innermost circle of the scientific world. The prodigious honor was excelled only by an unforgettable meeting. How wonderful it was that William Crookes met the great Michael Faraday himself!

Faraday sought William out from the crowd, a rare and humbling experience. Faraday had kind eyes, but spoke with a clear and forthright voice. He had heard much of the young man, and saw much of his own life in William. He strictly encouraged the young man to take up the pioneering study of chemical spectroscopy, promising him that the greatest new chemical discoveries would there be made. William took that advice as from a master. Years later his prophecy would be fulfilled. Time had passed indeed.

Having thus recalled the great Michael Faraday, a bookbinder who virtually established the world fame of the Royal Society, Sir William added a few words in the way of tribute. “The great philosopher’s lecture on Radiant Matter was given in 1816, when Faraday was twenty four years old.” Remarkable! Faraday preceded every major scientific revolution by sixty years. He called for the lights. Were there, he wondered, any young hearts out in the audience of similar affections and intuitive skills? Were there any fervent and curious minds out there? But his eyes scanned about the room, spying out only those whose dispassionate expressions betrayed only a singular disinterest.

There was a time in which he had become angry with the exceptional lack of vitality among certain Society appointees, but gradually grew to understand this as characteristic of the aristocracy. The bored deportment of most who sat in the audience may have been the direct result of patronage and breeding, but was certainly not the result of artistic fervor and scientific temperament. These were the sons of patrons and traditional families, who merely occupied their elected posts. It was they who, through effete vanity usually obstructed the discussion portion of the Society Proceedings with antagonistic interruptions; although such questions were designed merely to reemphasize jurisdiction over the Society.

Of the illustrious Society and its message to the world at large, they seemed utterly incapable of offering anything in the way of adornment or enrichment. Sleek and self-composed, there was nothing in the way of scholarship in all their thoughts. There was no spark of curiosity, no scientific life in them. No love, no necessity to learn, to excel and advance. One heard the dour temperament in the affected congestions of their speech. Smug, arrogant, implacable, and reprehensible, he knew who they were very well. And while he would do his best to dissolve away that critical and elitist air with his animated bravado, he did recall his first hurtful encounters with the gentry.

GLITTER

The path of his life had produced a glory, but it had not been an easy journey. The long night hours, the dusty volumes, the long thought trails. These were internal struggles which evoked the deepest personal transformations. The enrichments of knowledge required a demanding discipline which could never be ill-spoken. The exhaustion of his effort and much labor was not without its wonderful reward, its divine response. One became radiant only after having endured “the process.” The dreams, hopes, failures, achievements . . . all those trials and errors formed a unique tapestry, whose current and flood required a unique willingness to press forward. Few of his elite schoolmates were willing to abide the discomforts of such intense desire for even a moment.

Class distinctions were very much alive and active in that day. It still is. Their repugnant and smug misuse of all others had a dubious distinction. It was world-famous! William recalled well the manner in which the aristocrats had never accepted his father. The status which they proscribed to him was that of a mere servant, whose talents and abilities were viewed as a resource for their personal service. Despite his wealth and dignified stature, the aged Mr. Crookes was never allowed into the inner confidences of that upperclass.

This mistreatment extended to young William. He had sensed it all around him in the College. There were those whose presence in the lecture halls had nothing to do with scientific passion, nothing at all to do with the need to learn. But there they were. In addition to this effrontery, he was often excluded from their social clusters. Since his father was a tailor, this was considered a mark of fundamental division, a blot on their potential social registration.

But William was indignant of these self indulgent traditions. He bore his father’s station as the greatest mark of honor. He espoused his father’s teaching, and taught his own children that only in prayerful effort and impassioned endeavor true greatness was won. Great men were made, not born. He would rise above his detractors in avenues, perhaps not in elitist isolation, but in achievement. When he was scarcely twenty two years of age, he was appointed as Superintendent of the Meteorological Observatory in Radcliffe. His life had been a walk in wonders. The new appointment, a straightforward confirmation of prayer.

Within two years df this installment as Superintendent, tragedy struck. His father passed away in the night. William was crushed, the family in disarray. William, being the eldest son, was now to rear and guide his younger brothers and sisters. They would forever look to him for morale, guidance, and comfort. He would look to them for solace. It was a position for which he was admirably suited, but the loss of his father deeply affected him forever after. The fortune, to which he was heir, was wisely invested.

He had learned a great deal from the German chemist, Dr. August Wilhelm von Hoffmann. It was with Dr. Hoffmann that William saw the value of every new scientific find. Von Hoffmann viewed each stray scientific fact and phenomenon as of paramount importance.

Every natural effect was observed and valued. Each was aggressively scrutinized as if it alone held some new secret to an entire world of industrial potentials. Crookes saw the validation of ideals which Faraday had quietly cherished. It was in the employ of von Hoffmann that William Crookes learned the German ethic of free enterprise firsthand.

He understood that German attitudes were not at all like the British ones in terms of class and stature, a surprising and strangely comforting discovery. The traditional system of dialogue between all classes, professions, and occupations, became the essential secret of Nineteenth Century German Technology. Lines of communications were opened to all for the good of all. This became too evident before 1870. In the meteoric development of chemical process and metallurgical applications, Germany had no equal in all of Europe. This was dangerous, and Crookes did not lightly esteem the imbalance of power in Europe. But his subsequent accomplishments had several trenchant motives, not the least of which was an importation of the German scientific ideal. One was the expansion of the working class ethic, and the extension of their rights in the realm. Another was the simple undoing of the aristocratic element in the scientific circles. Their obstructive influences had diminished every scientific revolution which defied their aesthetic. And what was their aesthetic? The methodical elimination of working class aspirations.

Restricting, limiting, and diminishing this dream potential among the lower classes was first achieved by restricting attendance in higher learning institutions. This rule also diminished the chance that working class persons would rise, if in mind only. This aristocratic rulership of knowledge was also the principle reason why Vitalism was so deeply despised among the British scientific aristocracy. But such knowledge as William was amassing through his potent expertise was neither going to be restricted or exploited by the rigid British structure on any level. Here he drew the line. The secret was contained in a simple notion: seek out the most obscure and strategic facts. Consolidate every bit of knowledge in that field of study. Prioritize the knowledge.

“In the practical world, fortunes have been realized from the careful examination of what has been ignorantly thrown aside as refuse; no less, in the Sphere of Science, are reputations to be made in the patient investigation of anomalies.”

ELEMENTS

[Crookes's] astute enterprising aims had as their first order of priority a self sufficiency without aristocratic rule or restriction. He would be independent and self-employed. “Owe no man anything” was the lesson. As his father was successful in the art of tailor craft, so he would reach independent success in the scientific profession. Von Hoffmann had been a good and thorough master. He taught him well by example, and had highly favored and encouraged William. I am sure he insisted on calling him “Wilhelm.” In the isolation and efficient production of new chemical substances, there were new fortunes to be made.

William Crookes saw that this theme and atmosphere so contributed to the German industrial power base that to deny it was foolhardy. Worse, it might someday prove deadly. Competitive Germany had thoroughly recognized these scientific potentials, and were quick to implement every fruit of technical achievement. His strong opinion was contained in the notion that scientific labor should be justly and amply rewarded. Valuable scientific knowledge was not a free tithe, no mere resource. His nation needed to implement the free enterprise theme as rapidly as possible.

Exploitation was no longer to be tolerated. The German approach did not prohibit the exchange of information between and among persons of different class. Not so in England, where scientists and their technologies were viewed by royalty as exploitable resource for the personal extension of profit and power. By the end of the same decade, Germany would outstrip the English industrial facility on several key grounds. By the time the aristocrats were roused from their self deceiving slumber of peace, the whole of Great Britain had been shaken to its patristic roots.

Throughout the early history of this laboratory, Dr. William Crookes devoted himself to the discovery of industrial applications. The industrial production of new products was his aim, but this goal did not prevent him from exploring the natural world of chemistry. He was forever investigating new families of chemical substances which might prove in the future to be of strategic industrial importance. This native curiosity permitted him to be first in the discovery of new elements, compounds, and their possible use in some burgeoning industrial complex. In 1859 he initiated and directed the publication of The Chemical News, a scholarly journal whose aim it was to stimulate both the professional and amateur chemists into a new industrial revolution. He remained its principle editor for several years.

Serious theoretical and industrial information thus flowed from him and to him. The flow of such material was timely. In this theme and approach, Dr. Crookes explored the strange properties of selenium, a new “light sensing” element. The year was 1861, and selenium was the focus of several intriguing discoveries. Photoelectric effects were observed, and the extreme sensitivity of selenium to various spectra promised new industrial frontiers. It would therefore be imperative to be the principle provider of information on the topic area. In the eventuality of new applications, industrialists would want ready information on the manufacture of selenium components. William was always in the lead, especially when the more mystifying aspects of Nature made themselves apparent.

His intuitions were well rewarded when, in the next decade, selenium became the principle means by which certain highly desirable electrical analyzing instruments were made possible. In the process of studying selenium, William succeeded in discovering a new element. The element thallium was discovered in 1861, the result of a spectroscopic study. He recognized its unique strong green spectral line. Here was the word which Faraday himself had spoken. Here was the rarest of privileges, an honor granted to a very few individuals. How curious and fortunate that he had been chosen to assume such an exalted scientific poise in science history!

The discovery had its industrial merits. Lucrative merits. Poisonous metallic thallium, a bluish-white element, was utilized as a catalyst in the industrial manufacture of benzene and antiknock fuels. In its other chemical uses, thallium found prime application in the manufacture [17] of flint, glass, artificial gems, scientific thermometers, mineralogical washing solutions, and pyrotechnics. In the following years Dr. Crookes developed sodium amalgamation methods for the commercial extraction of gold and silver from crushed ores, devised laboratory-worthy spectrum microscopes and polarization photometers, compiled planetary and stellar spectra, perfected astronomical photography, and hunted for new planets and asteroids.

So it was, in 1863, Dr. Crookes was elected to the Royal Society as a Fellow.

WHITE LIGHT

It was while investigating certain properties of thallium in vacuum (1873) that he chanced to observe a unique motional effect in a delicate torsion balance. The mere presence of light, whether from the sun or an artificial source, made impossible the routine task of weighing the element in vacuum. Dr. Crookes saw that, as soon as light was admitted into his balancing apparatus, the delicate device moved quite violently. In some cases, the torsion balance struck its containment walls. The mere presence of light so destabilized the delicate quartz fiber of his torsion balance, that he paused from this chemical study.

With external sources of illumination, he found that vacua of 40 millionths atmosphere allowed the most powerful rotation in the vanes. With internal sources of radiant heat, he found it possible to obtain much stronger rotations. These were observed (over 30 rotations per second) in hydrogen gas at 0.1 millionth atmospheres…a remarkable figure! The observation of movements with vanes coated on both sides in lampblack. . .a complete conundrum . . . could find few good explanations. Nor could the mechanistic theory attempt adequate explanation of the other numerous anomalies found in his study.

Deeper inquiry into the “mechanical action of light” led to a minor upheaval in the world of physics. The philosophical debate which discussed the “light pressure” remained a focal point for years, since a reversal of theoretical expectations was obtained. The fundamental anomaly which Dr. Crookes and others observed was that “light pressure” caused the repulsion of dark bodies, and the attraction of reflective bodies. This basic riddle occupied the thoughts of many physicists for several years. Dr. Crookes published his findings in a long series of articles and scientific essays; where the variables of vacuum, substance, vane shape, even or uneven surface heating, and applied spectral energy were each studied with the utmost care. (The complete record of his meticulous research may be obtained in collated form a. DeMeo).

As regard to the anomalies which he observed, Dr. Crookes was bold and decisive. “In some of the observations, the results accorded with theory; and although I could explain most of the anomalies, there were irregularities which seemed to point to another influence…” Another influence? To what influence did he possibly refer? He had eliminated all of the mechanistic variables with elaborate shields and baffles. In fact, these inconsistencies were never solved and, with attempts to give answer according to the mechanistic theory, were entirely unsatisfactory.

The prevailing view among physicists was that the opposite vane rotations and other behaviors were all the result of molecular bombardments within the glass bulb. Varieties of mechanical dynamics (gaseous flow, viscosity, “creep,” recoil) along vane surfaces were cited in explanation of each anomalies. But each such puzzle required new and (sometimes self-contradicting) applications of the mechanical principles. The glaring inability to provide satisfactory explanations for key phenomena lent an increasing number of scholars to assail the mechanistic view itself. Accusations of the obvious deficiency in this view, especially in explaining the newly discovered phenomena of the day, represented the first in a series of major failures.

The mechanistic view was shown to be inadequate in such cases as regards various phenomena of light and other radiant forms. The trend to save “mechanism” continued through the Twentieth Century. Renewed interest in this episode of scientific inadequacy has evoked response from several researchers such as Dr. James DeMeo. This esteemed researcher and author considers the strong likelihood that such anomalies are entirely due to more vitalistic influences. The possibility that the anomalous results of Crookes were entirely derived from external influence of his own presence (i.e. of biological energy) has provided the most potent reevaluation of the phenomenon to date.

TOYS

In all of these important considerations we see that the mechanistic view and its explanations usually results from highly valued topical effects of least importance, caused by more dominant fundamental energies of Nature. Yet it is well known that Sir William inclined more toward these vitalistic possibilities, having observed motions on his own approach to the device. And, while never publishing his deeper inclinations on these issues, it is known that his study of paranormal forces were commendable in his employ of numerous sensitive apparatus . . . not the least of which was his Radiometer.

The debate on these “light pressure” anomalies prompted Dr. Crookes to bring the effect out of the academic halls and into the public forum. His development of the Radiometer for serious scientific use was a matter of scientific record. But this serious application did not limit his wonderful imagination from teaching children of its marvels. So delightful was the Radiometer, or “light mill” as he often called it, that an inexpensive version was developed for toy shoppes. The small scientific “toy” has remained both a curiosity and amusement since its first appearance. Of it Nikola Tesla gave fond homage, referring to the delicate design as “the jewel of motors.”

This first of many such “toys” became a distinct Crookes trademark, an ultimate “soft” vengeance. “In this realm of marvels, this wonderland [18] toward which scientific enquiry is sending out its pioneers, can anything be more astonishing than the delicacy of the instrumental aids which the workers bring with them?” Dr. Crookes was relentless in his provocation of the scientific aristocracy. His deliberate conception and deployment of a great many such “toys” was directed at their fancies. He would haunt both them and their children . . . with scientific “amusements” and “toys.” Crookes was the great scientific toy maker, but delighted in presenting them to those who would acquire them as curiosities.

Simultaneously cunning and humorous, the designs produced for his laboratory a steady source of capital. They also accomplished their primary task of preserving the various vitalistic conundrums everywhere. Crookes was especially delighted that the aristocrats perceived these as amusing devices to purchase. With his guidance, and the “skillful manipulations of my friend, pupil, and associate, Mr. Charles H. Gimingham,” the manufacture of a vast laboratory demonstration assortment was offered to the scientific community at large. Both in England and abroad, in America, sales of these marvelous and glittering Victorian designs brought in an important steady revenue. These designs were distributed in North America by James Queen and Company, a scientific supply house based in Philadelphia.

BLACK SPACE

Sir William’s scientific approach differed from the growing convention. His approach appealed to the philosophical aesthetic, rather than to the engineering theme. His demonstrations were never intended to represent miniatures for technological exploitation. In the Victorian tradition, experimental models and demonstrations represented philosophical statements. Each was made to consolidate some principle, to embody an idea. Experimental models were statements in solid form. Such devices were therefore always referred to, not as industrial appliances, but rather as “philosophical toys”; his elegant and final answer to each challenging polemic.

Sir William delighted in contriving such designs in order to provide wordless proof of each thesis. In 1877, he began his most world-renown series of researches into the discharge of high voltage electricity through spaces of very high vacuum. The automatic mercury pumps of Herman Sprengel were much improved on behalf of Dr. Crookes, again by Charles H. Gimingham (1877). It was this improvement which stimulated the new and thrilling research, since prior to this time, the reasonably attained vacua were insufficient to produce the effects which were historically first obtained by Dr. Crookes.

His first major discovery was one typical of the style and flair by which he would be best remembered. Bringing the vacuum to its ultimate degree, he observed a mysterious “dark space”. This was the metaphor which most captivated his scientific attentions, a symbol and representative of space itself. But what was in that dark space? He called again for the lights to be withdrawn. They had seen his preliminary demonstration of phosphorescence, but had they comprehended the meaning of those phenomena? Had they pierced through to his exact intimations concerning that phenomena?

Were they able to realize that no phosphorescence, no light is ever emitted unless substances are completely wrapped and permeated in a blanket of absolute darkness? Did they appreciate that every condition of earthly light was first predicated in every instance by a permeation of radiant black space? His voice again rang into the dark space of the Hall. “I will endeavor to render the ‘dark space’ visible to all present. Here is a tube having a pole in the centre in the form of a metal disk, and the other poles at each end.” The large barreled tube which he stood near on the table was fitted with a disc-shaped central cathode, facing two opposed anodes; one at each end. Current was applied.

“When the exhaustion is good and the electrical pressure is high… the dark space is seen to extend for about an inch on both sides of the cathode.” The luminous gas residue withdrew to the anodes, being tightly squeezed upon their metal surfaces. But the dark space remained. Clearly, all matter had been forced away from this space, otherwise it would be glowing with light. In the dark space were rays whose power “…radiating from the pole with enormous velocity, assume properties so novel and so characteristic as to entirely justify the application of the term borrowed from Faraday… that of Radiant Matter.”

There were those who had always mistakenly believed that his Radiant Matter was simply composed of electrons, even as J. J. Thomson had sought to prove. But Sir William could never have disagreed more. To him, the dark space was filled with “dark light,” the precursor to every form of light known to the world of physics. It was the energetic presence of this dark light which provoked the phosphorescence of any substance placed within that dark space. As he was about to prove again, the dark space was completely devoid of inert, or massive particles. He would now separate the negative charges from the neutral dark light particles. The next few demonstrations were therefore designed to highlight his original statements concerning cathodic rays and precursory light.

The younger and more acrid members of the Society, the posh appointees of fashion and advantage, remained completely unimpressed with his outpourings. Their affections forever fawned among the acceptable conventions, since this poise always seemed to preserve and a greater social favor . . . an assured measure of decorum. For them, learning was unimportant. Face and keeping face was all.

Nevertheless, he remained courtly, noble, and somehow impossible not to watch. There was an unmistakable luminosity about the man which was also difficult to deny. It seemed to brighten whenever he spoke. “It is not unlikely that in the experiments here recorded maybe found the key of some as yet unsolved problems in celestial mechanics . . . we may argue from small things to great.” The audience saw his vague outline moving to the far side of the proscenium. They turned to see. Sir William now stood among a select series of vacuum tubes, also now decades old. With these large demonstration vessels, he would provoke his detractors into a renewed revelation of Radiant Matter.

EMERALD

He opened this section of the lecture with a simple statement. “To those, therefore, who admit the Radiant form of matter, no difficulty exists in the simplicity of the properties it possesses, but rather an argument in their favor.” He stood behind a second apparatus, a large V-shaped vacuum tube, and applied the voltage. “You see that the whole of the cathode arm is flooded with green light, but at the bottom stops sharply, and will not turn the comer to get to the anode…. Radiant Matter absolutely refuses to turn a corner.” By this it was understood that cathodic rays did not behave like ordinary electric charge, which would have eagerly sought the positive terminal. Many imagined that the high terminal velocity, imparted to these rays on ejection from the [19] cathode, actually constrained the rays from seeking the electropositive terminal. They remained unconvinced that the rays were “rays of dark light.”

A third large bulb stood near this V-shaped tube. This bulb had a cathode which had been sealed in the side. Two anodes had been sealed at opposing angles and at differing distances from this cathode. The current was applied. “Notice,” he said, “the rays fall on the opposing side of the bulb, and produce a circular patch of green phosphorescent light. As I turn the bulb round you will all be able to see the green patch on the glass. Whether I now electrify the top or bottom anode, the rays remain unmoved from their path…. Radiant Matter darts in straight lines from the negative.”

The positive proximity to the ray path did not alter the beam in the least. Were these the light mass particles claimed by Thomson and his adherents, this ray path would have bent to the closer anode. But it did not. He beamed nearly as bright as one of his tubes. Now he turned to a very large diameter tube. His fourth proof for the existence of cathode light rays. It was long, fitted at one end with a split cathode. At the other end was a single anode. Through the center of this tube, a phosphor coated card was placed for the visual inspection of cathode rays in their progress across the space. “If the streams of Radiant Matter are simply built up of negatively electrified particles, then they will repel one another. But if the streams are neutral, then they will proceed independently of one another.”

Now switching the current on, two straight and brilliant green rays traced their thin paths across the card. The surprised reaction in his audience was delightful! Both rays moved independently of the other. Each touched the anode separately. Though ejected from the cathode, such emission did not conclude negative charge. Here was the proof. Sir William showed again that Radiant Matter was a neutral, light like form of energy.

A fifth globe used a large concave cathode with an opposed planar anode. Between this cathode and its small anode, a strip of silver-white metal was poised on a sealed support wire. The globe was very large in size. “The bright margin of the Dark Space becomes concentrated at the concave side of the cup to a luminous focus, and widens out at the convex side. When the dark space is very much larger than the cup, its outline forms an irregular ellipsoid, drawn in toward the focal point… the whole appearance being strikingly similar to the rays of the sun reflected from a concave mirror.”

“You will notice that the rays which project from the cup, and which cross in the centre, have a bright green appearance… the intensity of the color varying with the perfection of the vacuum.” That strange green light, what equally bizarre properties it displayed! “The cup is made of polished aluminum, and projects the rays to a focus. In this tube, the rays focus on a piece of iridio-platinum, supported in the centre of the bulb.” The globe was ingenious, an embodiment of genuine insight. Those who long believed the inadequacy of the Victorians regained a lost admiration.

“With only a slight application of the current, the interposed metal strip suddenly became white hot. I increase the intensity of the spark, the iridio-platinum glows with almost insupportable brilliancy, and at last melts.” This demonstration showed a remarkable and uncommon property of Radiant Matter. In its apparent ability to defy the Faraday electrostatic laws, it could not be composed of negative particles. Leaving internal surfaces in converging lines, electrons could never be brought to such a tight focus without producing noticeable repulsions.

This radiant behavior more exhibited the characteristics of light than particles of matter. The radiant extension of the material shape into the vacuum was visual. It took the form of straight and continuous lines. On closer examination, and in taking consideration of electrostatic principles, here was a very different kind of ray than that which J. J. Thomson quantified.

RADIANT MATTER

Sir William again called for the lights. His coup-de-grace was a large and bulbous “electric” Radiometer. This demonstration Radiometer gave a most remarkable demonstration of the mechanical energy exerted by the dark space itself, a singular anomaly. “The best pressure for this Electrical Radiometer is a little beyond that at which the Dark Space extends to the sides of the glass bulb.” He attached the leads with ginger delight. Here was a “toy” which he especially enjoyed sharing with others. “On continuing the exhaustion, the Dark Space further widens out and appears to flatten itself against the glass, whence the rotation becomes very rapid.” Current was applied, and the vanes spun themselves into a blur.

“You perceive the dark space behind each vane, and moving round with it?” When the power was increased, the blackness covered the vanes completely, and the vanes began to rotate into an amazing blur. Here was true light pressure. Light pressure in the apparent absence of any material agency. In this device, motion required the mere presence of the dark space. But what was in this special space? Was it the literal extension of the cathode into the ultravacuum? Was this a revelation of the continuity of matter in space? How did vacuum and electrostatic charge now combine to expand the material volume of the cathode, revealing it as force? This was nothing less than the Reichenbach thesis, where matter and its diverse qualities extends throughout space.

“Here we have actually touched the borderland . . . where Matter and Force seem to merge into one another, the shadowy realm between Known and Unknown, which for me has always had peculiar temptations. I venture to think that the greatest scientific problems of the future will find their solution in this Border Land, and even beyond; here, it seems to me, lie Ultimate Realities, subtle, far-reaching, wonderful.” What an epithet! One might well draw the title for a scientific journal from his words.

The vacuum tubes thus provided a most potent visual means for elucidating each of these concepts. This visible proof, which the mind grasped, offered the noisy intellect perhaps more analytic substance to disannul. But the combined effect of the performance would force the intellectual process to relax, while the holistic sensibilities once more brought in true and whole vision. The analytic process simply disintegrated the world into nothingness. This qualitative grasp represented a larger consciousness. As often as he shared this demonstration model, his audiences remained completely enthralled. He knew the all too human need for colors, sounds, and motions … for sensation. Sensation, whole experience, was the proper use of the mind.

His experiments had revealed to him that matter and material aggregates were supported in their very existence by non-inertial form. This what the fourth state of matter represented, and this is precisely why it was so vehemently rejected. Here was the heart of Vitalism yet again revealed! In this revolutionary view, molecules and atoms vibrated about a lattice of “continuous matter.” The mobile particles of inertia were simply associated with these continuous solids, and were not themselves the real forms we knew as matter at all. Platonic solids [20] contaminated by inertia! Collectively, the demonstration was a marvel, a true philosophical argument in the best Victorian tradition. His last display caused quite a commotion.

The younger aristocratic members, those who most sought to maintain their composure, were now shifting ever so slightly in their seats. He noticed this with glee. How tragic! They refused to so much as grant him any facial expression whatsoever, a too common conceit. Noticing the ill-cloaked irritation of his young aristocrats, Sir William chuckled. He did not care so much that they were vexed, as much as he was delighted that his point pierced their defense. For them, his beaming joy was detestable. To this animosity they were entitled. Nevertheless, amor vincit omnia!

Were they aware of their German counterparts, whose industrial complex was about to march across Europe to the very borders of England? Alas, theirs was a sleep of ages, from which they would soon awaken in frightful need. But there would now be no prating command for protection and service. Science and other working class “servants” would now exact their wage, their price. Among the burgeoning scientific class, those who had suffered so much indignity, there was no urgent obligation to the dwindling Empire. The free option to emigrate to North America was now forever their chief tool of threat. And if it was not possible to maintain the common human right in England, there was dignity, honor, and profit to be made over that westward sea horizon. Command would remain among those scientifics, those laboring minds whose experience in life had not known idle advantage.

RARE EARTH

Sir William had undertaken a thorough research on rare earth elements in 1883, a field of study which would have enormous strategic and industrial importance in the mid-Twentieth Century. His original research in this capacity brought him to a consideration of radioactive phenomena and the possibility of elemental transmutation, yet another term which the proud desperately wished to eradicate from the scientific register.

But Dr. Crookes was the first to observe that elements contain isotopes, noting that pure elements were composed of differing atomic weights (1886). His conception of transmuting the elements was therefore founded on sound reasoning, and clarified observation. Each of these notions were in part realized with the discoveries of Ernest Rutherford.

Sir William began to consider the possibility that all matter, all elements, were “built up” by a primordial aether. Where would such a primordial aether be found? Sir William held out his hand toward his tubes, emphasizing the effects which had just illustrated the heart of his dissertation by wordless example. His glassy globes and bulbs, with their twirling little mica vanes, now sparkled in the eyes of those who watched them almost as much as did his rimmed glasses!

The prevailing “old school” view was indeed here, embodied before them. Sir William was a sprite, a truly “aethereal” character! Cheerful, merry, beaming, brilliant, lighter than air, he appeared to be aglow with the same white light seen in his mineral tubes. Equipped with his collection of unearthly globes and radiant crystals, he glittered a starry message of dreams… without words. Most realized that they had, quite unawares, fallen into one of the delightful little games of the grand old gentleman. Each slowly saw where he was guiding their vision. A few resisted, could not follow. They tuned their hearts away, and were instantly recognized. He was aglow, spying them out as if by magic. Most enjoyed the prospect of allowing him to guide their mind’s eye, and were drawn into his hopeful sphere of influence for a few more moments.

Those who best remembered the melody of his voice and life remembered a sense and mood from another time, from childhood’s forgotten world. The old gentleman spoke, a dark line from Royal Society history. “Faraday pointed out that matter existed in four states: solid, liquid, gas, and radiant. He stated that as matter ascends in the scale of forms …it does not cease at the gaseous state. But the greater exertions Nature makes at each step of the change becomes greatest in the passage from gaseous to the radiant form…” He was not now averse to making formal statements concerning the luminiferous aether. Besides the fact that they had spent the evening observing effects-in-miniature of this aethereal gas, it was also an air in which he seemed to live and move quite comfortably.

Indeed, “the phenomena in these exhausted tubes reveal to physical science a new world …a world where matter exists in a fourth state, and where the corpuscular theory of light holds good.” He called attention to the strange green light, that which was observed with each manifestation of cathode rays. The green light had peculiar and persistent qualities. “This green phosphorescence is a subject which has occupied my thoughts, and I have striven to ascertain some of the laws governing its appearance.” This statement sent some of their minds reeling with implications.

“The spectrum of the green light is a continuous one …no difference can be detected by spectrum examination in the green light, whether the residual gas be nitrogen, hydrogen, or carbonic acid.” Most physicists had concluded the green light to be a property of the bombarded glassy matter. Its spectral lines were taken as proof of the “excitation” theory. But now Dr. Crookes was highlighting his spectral study, finding the curious constancy of that light regardless of gas or glass. Was this not some indication of the existence of a new “ultragaseous” element?

For some, the very admission of an ultragas was instantly recognized. But the lecture had perfectly led to this realization, and was whole in every aspect. From these elevated vantage points, one could hardly argue the existence of the luminiferous aether!

He continued, emboldened by the sense that the audience had entered that absorptive stage, where deep and permanent impressions could be made. “Between the gaseous and the ultragaseous state there can be traced no sharp boundary; the one merges imperceptibly into the other …nor can human or any other kind of organic life conceivable to us penetrate into regions where such ultragaseous matter may be supposed to exist.” Most mortals at least could not endure the ethereal air as he so effortlessly did.

“The position of the positive pole in the tube scarcely makes any difference in the direction or intensity of those lines of force which produce the green light, and this green light is distinguished from ordinary light…it cannot be wrong to here apply the term emissive light.” The glowing globes had each spoken the thesis for him. He merely repeated those statements which he had published so many years ago. But no matter now, all minds asked the same question. All knew the identity of that pure light which issued forth from his highly electrified cathodes. There could be no question now. Those whose minds now grasped the whole message of the one who stood before them, fell silent. Why had no one ever considered these facts? One saw around his [21] words, and conceded without a single protest. The unmistakable ring of truth.

Sir William suddenly appeared to have now satisfied himself that his message was well received. A teacher could not hope for more than this. For a few brief moments, the Hall felt silent.

“Time has not allowed me to undertake the whole of the task so vast and so manifold. I have felt compelled to follow out, as far as lay in my power, my original ideas. To these collateral questions, I must now invite the attention of my fellow-workers in Science. There is ample room for many inquirers.” It was not until a few began to clap and shout sharp words of approval that Sir William looked down once more. He smiled again and looked among them all. Standing among his glittering and delightful toys, he nodded his thanks at their approval. The green light, the melodious voice, the twinkling eyes, the silvery air, all remain suspended in memory.

Sir William Crookes left the spinning, glowing, scintillating magic of his wonderful little toys in the springtime. Nikola Tesla never forgot the date when his dear mentor and friend departed the material world. Shedding aside the crusader’s lantern to those in the scientific world, he took to the stars – the date was April 4, 1919. Those who grew to cherish his memory lifted his lantern before it fell into the relativistic dust. In so doing, one felt a twinkling joy where there should have been sadness. The great man’s passing left a sparkling tracework, and yes, like the joy which suddenly quickens and stimulates in the midst of night, it twinkles still!

References

All quotes were taken liberally from the following excellent sources:

- Selected Reprints of Articles Related To The Mechanical Action Of Light And The Radiometer, Sir William Crookes, (compilation reprint) by James DeMeo, Natural Energy Works, 1994.

- The Phenomenon of Spiritualism, Sir William Crookes, London, 1874, The Quarterly Journal of Science, (reprint Health Research, 1972).

- Radiant Matter, Sir William Crookes, Nature, 1879 (reprint Electric Spacecraft Journal, 1995).