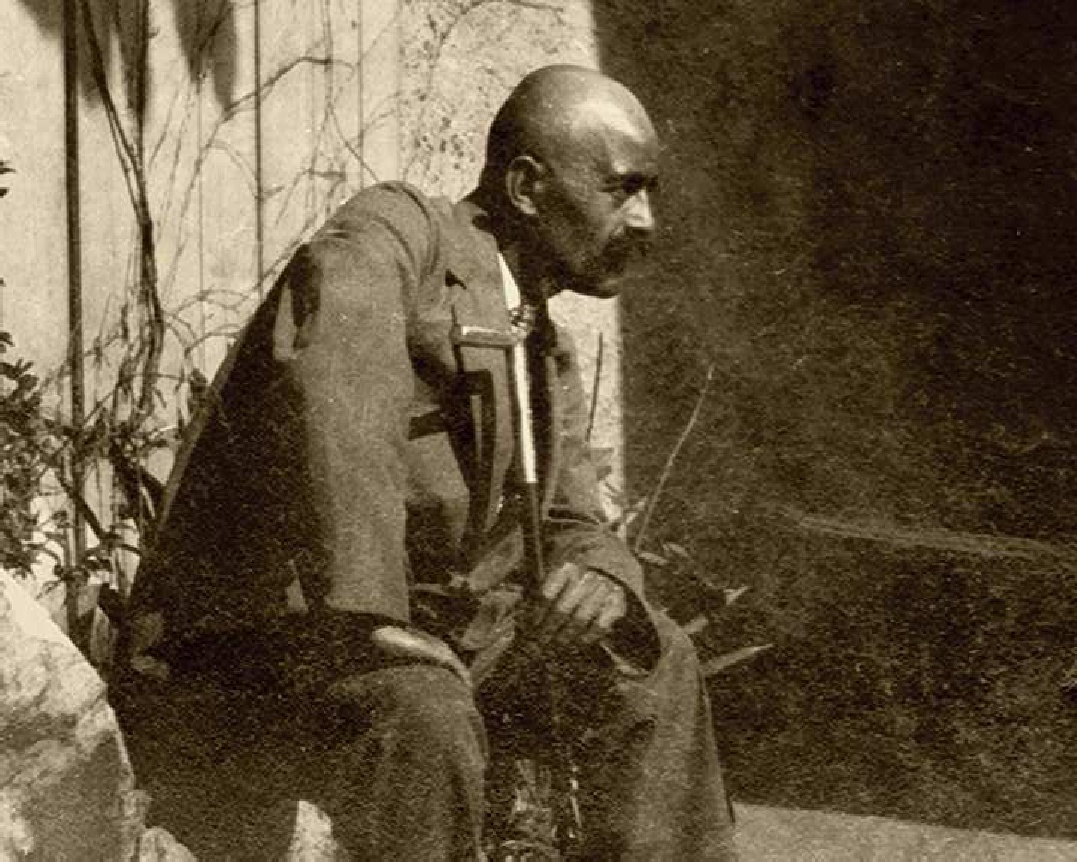

G.I. Gurdjieff was born in Alexandropol, a Greek port on the Aegean Sea on January 1st, 1872. Even at an early age he displayed a keen interest in what is loosely called the supernatural. Becoming baffled at the seeming contradictions between observed facts of everyday life and the teachings of religion, science, and philosophy, he made up his mind to resolve these contradictions for himself and organized a small group called the "Seekers of Truth". Soon afterwards they began a series of long and arduous journeys which eventually took them to Africa, Persia, Turkestan, Tibet, and the Far East, including the Indonesian archipelago. They visited monasteries, groups, and individuals, in fact anywhere they could find the knowledge they were seeking.

During nearly twenty years of investigation and experimentation, Gurdjieff and his "Seekers of Truth" studied and tested practical methods for the development of the psychic and psychological resources of man, most of which are usually latent and considered unnatural or undesirable in the West. A portion of these findings have been published but many are known only to Gurdjieff's disciples, being passed on from mouth to ear.

Returning to Europe from the last of his trips, Gurdjieff opened a school of training, development, and research, in which he continued his experiments and further study of the "28 categories of types existing on earth." Note should be made of the experimental approach which has always been part of Gurdjieff's system. He experimented not with things but with human beings and their inner states. His institute had a varied career, but, as a result of two serious accidents, his belief that mankind was facing a period of unusual tension, and the chilling foreboding that his time was short, Gurdjieff closed the institute. He then applied himself with incredible concentration to writing a series of books, hoping thereby to lead more people to an understanding of his teachings and methods.

Gurdjieff's writings are in three series, each corresponding to and confined to separate levels of understanding. The second and third series are available only to those working with authorized teachers. The first series, "All and Everything," is the only one which has been published. The writer of this review is not an authorized teacher.

"All and Everything," published in 1950, is an extraordinary book, and contrary to the second and third series, is extraordinarily difficult to understand. The subject matter and style are bewildering and the introduction of new terms of grotesque spelling are so frequent that new readers are tempted to quit after a few chapters, despite the warning in the first chapter that they will not find the kind of language (or soothing narcotic) they are accustomed to in other books.

Other barriers are not intellectual but emotional, and arise from the drastic manner in which Gurdjieff deals with the holy cows and sacred concepts [2] in the mind of the average man. It is painful to have our cherished ideas exposed as being false, illusory, or capricious, but this happens if the reader continues with Gurdjieff's teachings. The waking-up process on which he places so much emphasis can begin with a serious study of "All and Everything."

The main character in the book is Beelzebub, who revolted from what he thought to be an injustice in the universe and was thereby banished from our solar system. Returning to earth from time to time in a space ship, Beelzebub describes these visits to his grandson, Hassein, and uses the history of mankind on earth to illustrate the need for developing the power of impartial reasoning and compassion for the suffering.

Man is depicted as living in a pathetic, dream-like state where the so-called conscious part of him is out of touch with Reality. Even when he is awake in the usual sense, man spends most of his waking hours in a state that is a semi-trance or a complete trance. His actions correspond not to the actions of a fully awakened, responsible Being, but to the actions of an automaton or mechanical man. Even worse, these "three-brained-beings", as Beelzebub describes us (pp. 145, 441, 480, 491, 777-780, etc.), have learned to trust the guidance of the part that lives in this trance-like state and do not know how to enter into or experience actual consciousness.

The reason, Beelzebub tells Hassein, for the existence of this deplorable condition where man lives almost entirely in a dream state, is because of the presence in our remote ancestors of an organ called Kundabuffer (pp. 85-90, 111-114, 353-359, etc.). The effect of its presence has resulted in an inherent disposition in modern man toward self-deception and the inability to see himself as he really is.

Most readers reject this as being absurd and it is natural for them to do so. Even Beelzebub himself warns Hassein that the pictures he gives of man "doubtless seem to you the fruit of fantasies of an afflicted mind." And it is so only after long periods of observation of our mental, physical, and emotional actions -- without emotional bias, known in the system as Self Observation -- that we readers begin to see the truth in Beelzebub's statement.

There are sections in the book which state that man's actions are merely reactions, that men are mechanical, automatic, and without inner direction. These statements are particularly disturbing to most readers. In "The Search for the Miraculous" no less of a disciple than Ouspensky tells of his decision to "stay awake" (remain in a state of awareness) for a certain period of time in order to test Gurdjieff's teaching, and his own inner power and force to do so. Two hours later he found himself in a strange section of St. Petersburg [3] without the slightest recollection of how he got there and of what had transpired in the meantime. Yet readers with not one tenth of Ouspensky's knowledge and development have the vanity to believe that they can stay awake, that their actions are not mechanical, and that Gurdjieff is wrong and undoubtedly a black magician for suggesting such outrageous ideas. Were Darwin, Galileo, and Copernicus also black magicians?

But those who follow Gurdjieff's teachings come to realize how delightfully easy it is to drug ourselves with imagination, to dream colorful lies about ourselves. In another reference Gurdjieff describes people acting and imagining that they are peacocks when they are really "old turkeycocks." The blunt truth is that a turkeycock can never become a peacock, but our imagination tricks us into believing that some day -- in some purple mist of tomorrow -- it will be possible. But the most harmful feature of this wrong use of imagination, Beelzebub says, is the waste of time and precious energy -- time and psychic energy wasted forever, gone "down the sink" as a result of living in a trance-like state the major part of our lives. The shocking total of this can be learned by Self Observation. By being content to imagine something instead of striving to be something we waste the psychic energy and force which could be used to raise ourselves to a higher level of existence.

Thus, if we are old turkeycocks, we should not strive to become imaginary peacocks, but instead become the best turkeycocks in existence. If we are peacocks, strive to become the most resplendent peacock in existence.

Perhaps the most chilling part of the teachings, particularly to those who have studied other systems, is Gurdjieff's insistence on the necessity of realizing and experiencing our own "nothingness" before beginning the process of becoming "something." In other schools this equates with "the dark night of the Soul" and is considered an advanced stage on the path. The process of being taken apart and reduced to "nothingness" by a teacher before being put back together again, minus an accumulation of physical, mental, and emotional debris, is so painful that few of those who have cut their spiritual teeth on the less drastic systems ever complete the process.

Why don't they? Because they refuse to recognize the need for it. It is so much easier to read book after book, attend lecture after lecture, anything to avoid getting down to the difficult task of "working on oneself." The end result after years of study is that these advanced students cannot contain their wandering minds for twelve seconds. It is much easier and more pleasant for them to imagine they are peacocks -- or advanced students -- or even great souls -- whatever their private conceits, than to do thirty minutes of work "on oneself."

Gurdjieff met hundreds of such in his travels, and in "All and Everything" he states categorically that the most universal and undesirable factor encountered by him in his long quest is that which manifests as vanity and self-conceit. So he announces his determination: "To quarrel ruthlessly with all manifestations dictated in people by the evil factor of vanity present in their beings."

To some extent Gurdjieff's life is one of tragedy. He saw years of work and preparation broken to pieces by the raves of two world wars. He saw Gurdjieff the man and his teachings maligned and misunderstood, particularly by those who would not venture out of their comfortable illusions to test his teachings.

It should be noted here that the central and significant part of his teachings, with the exemption of one part called the Reciprocal Maintenance of Everything Existing, can be tested, accepted or rejected by anyone who will take the trouble to try them out.

"All and Everything" is not easy to read or to accept. At times it seems incomprehensible, particularly to those studying without a teacher. Yet I believe it can be done and those who are able to master it peculiar style come to realize that Gurdjieff has given mankind a body of truths. When properly used these enable the reader to divest himself of illusions about himself and his place in the world. Moreover, Gurdjieff shows what man must do so that "things will be done by him and not to him."

Gurdjieff died in 1949. Before passing on he discussed the difficulties confronting his disciples and indicated that another teacher would follow him. In 1957, J.G. Bennett, highly respected by Gurdjieff's followers for his intellectual and spiritual attainments, said that he believed the new teacher was incarnated in the body of Pak Subud, an Indonesian mystic. Other equally respectable disciples of Gurdjieff do not share Bennett's enthusiasm for Subud, and continue to follow the traditional methods of the system.

If it develops that Bennett is right, it is the writer's view that the coming of Subud marks the end/beginning of a Time Cycle in the teachings. There is a striking parallel of this kind in the history of Buddhism; that is, the change from the spartan-like methods of the early Theravada Buddhism to the more readily accepted Mahayana Buddhism, i.e. the change from regeneration by personal effort to regeneration by grace.

* * *

Your editor wonders if Gurdjieff didn't have in mind those metaphysical dabblers who like to read and read and read when he wrote "All and Everything." It rambles on and on for one thousand two hundred and thirty eight pages! It was published by Routledge & Kegan Paul, Ltd., London, 1950. We do not have any to sell here at Headquarters. I challenged Associate Walsh to come up with a readable review of "All and Everything" and I think he did a good job. There seems to be considerable interest in this controversial teacher among our members so there will undoubtedly be more about him, pro and con. One Associate claims to have studied with him in New York and also to have spent some time at Gurdjieff's Chateau school at Fotainebleau, France. Her experience should be of interest to all of us. When she and I can get together and reduce them to readable writing they'll be published in the Round Robin. "Men and women with pronounced critical difficulties and a marked intelligence became his pupils," wrote Rom Landau in God is My Adventure, "Many of them parted ways with him, but they all admitted that Gurdjieff was one of the real spiritual experiences of their lives."

* * *

References

- Gurdjieff, Georges I. All and Everything: Ten Books in Three Series, of Which This Is the First Series. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1950. Print.

- Ouspensky, Petr D. In Search of the Miraculous: Fragments of an Unknown Teaching. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1949. Print.

- Landau, Rom. God Is My Adventure: a Book on Modern Mystics, Masters and Teachers [with Portraits]. London: I. Nicholson & Watson, 1935. Print. [Digital (PDF): <https://archive.org/details/godismyadventure032951mbp>]