Historical Myths and Truths

"The Declaration is a masterpiece of propaganda . . ."

Howard Mumford Jones

Lowell Professor Emeritus, Harvard

The Uranus-Neptune conjunctions of 1993 marked the beginning of a new era. The entire globe now stands on the verge of a New World Order — political, spiritual and astrological. Those convictions all of us hold most dear are not immune to the quantum leaps of consciousness inspiring the billions of humanity worldwide.

In our nation, the societal parent role is assumed by teachers and historians. As individual adult, we all share the same deep fears of abandoning our cultural past that we experience when leaving our parents. If a majority of a generation fear to take the plunge and renew their own mythology, cultural amnesia may ensue. The societal parent tapes of the previous generations may then develop into a cultural trance that hypnotized the next generation. The July Fourth myth was the foundation stone for generations of Americans during the 19th and 20th centuries. As Communism was demystified by Uranus (revolutionary) and Neptune (ideals) in Capricorn (the establishment history), so must Capitalism be reexamined. As Lenin was demystified, so must George Washington be reborn in the light of factual history. Let us not forget that amnesia is a hypnotic state, induced by a mental suggestion most often originating from outside the ego consciousness of the subject. Those in positions of institutional authority within a society are its hypnotists. It is up to the supra-conscious moral impulses of the individual citizens who comprise the forthcoming generations to assume the responsibility of self-dehypnotization. Every human soul is mythological in its unconscious state of awareness. The questions, therefore, are not whether "to mythologize or not to mythologize," but rather "which mythologies" and "how will they be created and transmitted."

In the 1940's, Manly Palmer Hall revived Ebenezer Sibly's astrological chart cast for the late afternoon of July 4, 1776. Although he was a contemporary of the founding fathers, it has not been demonstrated that Sibly's information source was any other than the official published version of the Declaration and the comments of Thomas Jefferson, its primary author.

Secret Journals

The testimony of Thomas Jefferson is powerful, and yet as early as 1884, Mellen Chamberlain proved that Jefferson (as well as John Adams and Benjamin Franklin) was inaccurate in his recall of the events surrounding the Declaration. By the mid-1940's, Chamberlain's conclusions were universally accepted by historians. Chamberlain was the first person to examine the original manuscript minutes of the Journals of Congress, otherwise known as the Secret Journals. On July 19, 1776, they stated, "Ordered that the Declaration passed on the 4th be fairly engrossed on parchment with the title and style of 'The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America.'" An entry on August 2 stated: "The Declaration of Independence being engrossed and compared at the table was signed by the members."

The Cover-Up

When Congress published the public Journals, it purposely transferred the July 19 and August 2 entries to July 4 in order to cover up the fact that the vote for independence was not unanimous and the declaration was not signed in the heat of an all-consuming patriotic passion. Yes, it was politics as usual — even back then with our own Founding Dads! Paul Leicester Ford, editor of The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, openly acknowledged that the published journal was "fabricated." After examining Jefferson's "Notes," Hazelton announced that they had been written at one sitting sometime after Jefferson retired from Congress in September 1776. Charles Warren believes that Jefferson relied on the official published Journal of Congress to jog his memory, and was unknowingly [20] led onto the path of error. One wonders how a brilliant mind like Jefferson's could think the eloquent phraseologies of unalienable rights in one moment and then instantly forget the chronology of their acceptance and approval by Congress. What's even more suspicious is that John Adams and Benjamin Franklin also gave similar public testimonies about a July 4th signing. Privately, however, John Adams had written a letter on July 9, 1776 stating: "as soon as an American seal is prepared, I conjecture the Declaration will be signed by all the members." How could the three brightest minds in America forget the actual events surrounding Independence, with each making the same error? Theoretically it is possible that Adams and Franklin were also led astray by the published Journals, but it is most unlikely. Their motive in altering the records was to make it appear to the public that the motion was adopted unanimously and without hesitation. Politically, what better action could be taken to assure public support for the venture? It is reminiscent of televised political convention where a motion wins by a large majority and is then ramrodded through to a unanimous vote by the party chairman. Years later, Jefferson commented that the Founding Fathers' intended purpose for the Declaration was as "an appeal to the tribunal of the world." In other words, as Garry Wills so aptly put it, "the Declaration. . . was not a legislative instrument . . . it was a propaganda overture, addressed primarily to France."

The Media Image

July Fourth was, in fact, made into one of the major media opportunities of the 18th century. The renowned painter, John Trumbull, became a key player in moving the minds of the masses. Photo opportunities were unheard of in those days; paintings were the photographs of the 18th century, and Trumbull was aware of their media impact. He knew how they remained etched in the American collective unconscious. He recreated the signing of the Declaration of Independence out of his imagination, exactly as he would have liked it to be. Trumbull was determined to perpetuate the myth of the Fourth of July for posterity. As we already learned, the signing of the Declaration occurred August 2, or more accurately, that's when it began. Fifty delegates signed on August 2, one on August 27, three on September 4, one on November 19, and the final signer, Thomas McKean, waited until 1781. By portraying all the eventual signers at one meeting, Trumbull reduced historical truth to obscurity and gave birth to a great American myth. It is no coincidence that Thomas Jefferson was intimately connected with the creation of Trumbull's painting. While Trumbull was visiting him in Paris, Jefferson proposed that he paint the Declaration and the proceeded to sketch the layout of the main hall as he remembered it. Using Jefferson's sketch, John Trumbull drew the layout for his masterpiece, which he completed in 1819, 43 years after 1776.

Fearless Dads?

The teaching of the Founding Fathers' fearlessness is also coming into question nowadays. Popular belief assumed that the American people knew the names of the signers when the Declaration was made public. The fact, however, is that only the signatures of John Hancock, President of Congress, and Charles Thomson, Secretary, were inscribed. The delegates withheld their names from the public for another live months after the August 2 signing because, if independence failed, their treason to the Crown might result in death. Not until after Washington's victory at the Battle of Trenton were the signers willing to go public!

Conclusion

The proponents of the July Fourth chart have Jefferson as their main witness, and yet they cannot rely on his testimony. His claim that the Declaration was signed on the Fourth is fictitious, along with the late afternoon time. The fact that the Fourth of July was the climactic moment of Independence is a myth; all the Founders did was tidy up the wording and stoically approve an articulate press release.

In actual fact, the Fourth of July is one of the more insignificant dates in American history! Daniel Boorstin claims that the Fourth of July's "commonly assigned significance is a mystery that may never be solved." Not until the highly coincidental, dual deaths of John Adams and Jefferson on July 4, 1826, did the date become immortalized. Garry Wills writes: "The first American histories of the Revolution did not find the Declaration an important part of the process . . . Detweiler thinks it did not become a generally accepted 'national charter' till after the War of 1812."

On July 4, 1776, John Adams wrote home to his wife: "The second day of July 1776 will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival." On the evening of July 2, The Pennsylvania Evening Post stated: "This Day the Continental Congress declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States." This was the first announcement that publicly declared independence, and it proves that July 2 was the climactic turning point of history. This day marks the moment that the Founding Fathers conceived a united States of America and (to prove the point) spelled its future name with a small letter "u". This first Declaration of Independence was actually the twinkle in daddy's eye, not the moment of the infant's first cry.

One People

Almost everyone has an opinion about the birth date of the United States, and rightfully so. Even the Founding Fathers had opinions — if only we could read their minds. It's important for all of us to realize that today, due to the vast quantity of firsthand documentation now becoming available, we can do just that! The following research is based on the contemporary vantage point of the Founding Fathers themselves; it seeks to unravel their opinions and attitudes. The primary sources include rarely published, well-documented quotations extracted from their writings and that of their contemporaries. Secondary sources are the writings of distinguished historians, experts in their specialized fields of study. This approach eliminates subjective speculation two centuries after the fact, allowing us to regain a real time perspective of late 18th century America.

The Nation's Birth

"The child Congress has been big with, these two years past, is at last brought forth . . . I fear it will by several Legislatures be thought a little deformed, — you will think it a Monster.""

Cornelius Harnett to Thomas Burke

November 13, 1777

Richard Henry Lee of Virginia boldly addressed Congress in the summer of '76, putting forth a radical resolution on June 7 that [21] called for independence from England and a plan of confederation, although the latter fact is commonly ignored. Both proposals were incorporated into this single resolution and simultaneously offered to Congress. Beginning in the nineteenth century, emphasis was placed on the dramatic act of separation that initiated the entire sequence of revolutionary events. Of course this makes for more exciting history lessons at school, but ultimately it detracts from the essential fact that in the minds of the Continental Congress such an emphasis would be misplaced.

On June 11-12, 1776, in accordance with the Lee Resolution, Congress created two committees. The first was headed by Thomas Jefferson and was to prepare a statement of independence. The second was headed by John Dickinson and was to draft a workable plan of union. Exactly one month later the Dickinson committee presented its report to Congress bearing the title "Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union." The ink that inscripted the Declaration had been dry a mere week.

It becomes immediately obvious that from the very beginning, it was the intention of the founding fathers to politically separate the individual states from England and then form a nation. The Articles of Confederation took their final form after sixteen months of soul searching and interrupted negotiations. They represented the first institutionalization of that unique American contribution to political science — federalism, the principle of divided sovereignty. Although the Confederation's national government did not receive the wider, centralized power base later delegated in the U.S. Constitution, it retained many of the powers of a modern nation (regulating weights and measure, creating post offices, borrowing and minting money, directing foreign affairs and declaring war / making peace, building and equipping a navy).

When the Constitutional Convention assembled in Philadelphia in 1878, the delegates were greatly influenced by Article IV of the Articles, absorbing much of its language into the Constitution's fourth article. Article IV is often called the "federalizing article" because it defines the relationship among the states, and between the state and national governments.

Articles of Confederation

"The free inhabitants of each of these states. . . shall be entitled to all priveleges and immunities of free citizens in the several states. . ."

"Full faith and credit shall be given in each of these states to the records, acts and judicial proceeding of the courts and magistrates of every other state."

"If any Person guilty of or charged with treason, felony, or other high misdemeanor in any state, shall flee from justice, and be found in any of the United States, he shall upon demand of the Governor or executive power, of the state from which he fled, he delivered up and removed to the state having jurisdiction of his offence."

Constitution

"The Citizens of each state shall be entitled to all priveleges and immunities of Citizens in the several states."

"Full faith and credit shall be given in each state to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other state."

"A person charged in any state with treas on, felony, or other crime, from justice, and be found in another state, shall on demand of the executive authority of the state from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the state having jurisdiction of the crime."

November 15, 1777 is, therefore, that isolated moment in history when the deal was made which established the United States of America. A new institution of federalism was initiated on the stage of world history. This is not the opinion of the author nor any other citizen of the 20th century. Instead it is the opinion of one of the prominent (but lesser known) founding fathers, Cornelius Harnett (see quotation above). Here was a man present on the stage of American history — at its very center. Here are the private written words of a contemporary Founding Father who was intimately involved in the drama of a renegade Congress running from its [22] enemy while it debated the Articles sentence by sentence. Like a quantum leap revisited from the turning point of America's destiny, the thought of Cornelius Harnett come back to haunt us.

From September 5, 1774, the Continental Congress had been serving as a provisional government without the legal sanction of a constitution. Until it was given proper authority by the states, the Continental Congress had been powerless to establish a permanent government.

Article One stated: "The Stile of this confederacy shall be The United States of America." Now the newborn's name began with a capital "U" instead of the small "u" it had been granted by the original heading of the Declaration of Independence. The well-publicized document of July 4, 1776 referred only to "the thirteen united States of America." As Librarian of Congress Emeritus, Daniel Boorstin, put it, "the uncertainties of the situation were expressed in the fact that the word 'united' . . . was treated as a mere adjective rather than as part of the proper noun." The Founding Father "used a small 'u' for united because it was still only a hope."

Not until after the victory of the Second Battle of Saratoga on October 7, 1777 were the Founding Fathers confident enough to establish a permanent government, including the capitalized "United" as part of its legally sanctioned title. Newborn nations are just like infants — the moment of birth normally coincides with the receiving of a name!

The Act of Conception

The approval of the Declaration of Independence is commonly accepted as the moment of the United Stats' birth. In actual fact, the thirteen colonies were declaring their independence from each other as well as from England:

These united colonies are, and of right out to be, free and independent states; . . . as free and independent states, they have full power to levy war, conclude peace, contract alliances, establish commerce, and to do all other acts and things which independent states may of right do.

Clearly, this document was not one of permanent union; instead, it declared that each colony had complete sovereignty over its own affairs. These new states united as allies against England in order to defend their own individual freedoms. John Adams wrote: "there have been in fact thirteen revolutions, for that number of established governments were overthrown and as many new ones erected."

Daniel Boorstin comments: "Independence had created not one nation but thirteen. At the time of the Declaration of Independence when John Adams spoke of 'my country," he meant Massachusetts Bay, and Thomas Jefferson meant Virginia."

The fact of the matter is that not one country, but thirteen new sovereign entities (nations) came into existence with the unanimous acceptance of the Declaration of Independence on July 19, 1776. Originally, each of the thirteen newly created mini-nations chose to establish its own private constitution before entertaining the dreadful thought of creating any kind of centralized government at all. It had been a simple matter to revolt against the King of England in comparison to the highly complex task of bringing thirteen individualized "ego-states" into any form of union. The very reason they had just broken loose from their Motherland was to be free from any form of higher power whatsoever. The level of statesmanship required to succeed with this second phase of the revolutionary experiment was much greater than that of the preliminary independence phase. Its all quite obvious — the Declaration of Independence demanded 23 days for its creation, the Articles of Confederation 16 months! The Declaration lacked the force of statutory law, the Articles of Confederation became the law of the land.

In the strictest legal sense, the vote for independence was an act of separation, not one of political union. From a traditional mundane perspective, the act of declaring independence form another political power is not viewed as the birth of a nation. Nicholas Campion, noted mundane astrologer, author, historian [23] and political scientist, addresses the issue of independence horoscopes head-on: "The attaining of independence by a state is therefore not a magical point at which it comes into existence . . . but a point at which power shifts irrevocably from the old to the new order . . . Many national horoscopes are set for the moment at which states achieve their independence from a colonial master, yet it is entirely false to describe independence as marking the foundation or beginning the stage."

Politics vs. History

Unjustly, the Confederational government has not been assigned a prominent role in our nation's history. Instead, it has been treated as an instigator of the social chaos and economic depression after the Revolutionary War ended. Noted historian, Henry B. Parkes, wrote: "The gloomy portrayals of this period have been derived mainly from the propaganda of the group working for a stronger central government . . . in many ways the Confederation period was one of rapid progress."

Who would think it appropriate to blame the Constitution of the United States for the 1930's Depression, the Saving & Loan bailout of the 1990's, or even the chaos created by gang violence in the streets? Today such outcries would seem ridiculous, and yet these are 20th century equivalents to the charges leveled against the Articles of Confederation by the Federalist party of the late 18th century.

Under the direction and control of the Confederational government of the United States soon became a success:

1) The Revolutionary War was concluded with a major victory;

2) an exceptionally favorable peace treaty was negotiated and vast, new territorial boundaries were secured;

3) the central core of the United States government's bureaucratic administration was established and developed;

4) the first executive branch of the U. S. government was created when four major departments were set up;

5) prosperity slowly returned despite the innumerable economic problems arising from the war;

6) the territorial lands issue was permanently resolved by the Northwest Ordinance — the first of its kind in all of world history — insuring equality between the a newly admitted states and the original states;

7) national citizenship was established: full-faith-and-credit across state lines, creditors from one state frequently sued in other states' courts.

The Confederational government's record was one of exceptional achievements, especially when considering that all these projects were implemented in just eight years! Typically, such acts become the foundation stones of nation; they are the fundamental reasons why the United States came into existence. Recorded history proves that the Articles of Confederation was not the do-nothing government some 19th century historians liked to portray. Although imperfect, it was a solid, credible government; otherwise it would never have received the massive amounts of foreign aid it obtained from France. Andrew C. McLaughlin, a leading authority on American constitutional government, wrote about the articles of Confederation: ". . . They were in many respects models of what articles of confederation ought to he, an advance on previous instruments of like kind in the world's history . . . as far as the mere division of powers was concerned, the Articles were not far from perfection. . ."

Despite the burdensome concerns of his private domestic life, Jefferson took part in the discussion which shaped the Articles of Confederation. On July 29, 1776 he wrote an urgent letter to his colleague from Virginia, Richard Henry Lee: "The minutiae of the Confederation have hitherto engaged us, the great points of representation, boundaries, taxation, etc., being left open. For God's sake, for your country's sake, and for my sake, come. I receive by every post such accounts of the state of Mrs. Jefferson's health that it will be impossible for me to disappoint her expectation of seeing me at the time I have promised, which supposed my leaving this place on the 11th of next month . . . I pray you to come. I am under a sacred obligation to go home."

Although committed to an August 11 departure, Jefferson stayed on more that another three weeks, until September 3. At this crucial time in his nation's development, Jefferson's commitment to the writing of the Articles of Confederation was uncompromised.

July Fourth '76 romantics like to portray the Articles of Confederation as inadequate and, therefore, invalid as our nation's founding document of state. It is historical irony of the highest order that the key witness testifying on behalf of the Articles of Confederation would be none other that the very author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson. He enthusiastically proclaimed that the confederation was the best government "existing or that ever did exist." Jefferson compared it to the governments of Europe, noting that the contrast was the difference between "heaven and hell." Although he ended up supporting the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Jefferson went on record as still preferring the Articles of Confederation! He viewed the Constitution as a substitute for America's original founding government: "Indeed, I think all the good of this new Constitution might have been couched in three or four new articles, to be added to the good, old, and venerable fabric."

The Founding Government is Our Present Government

The U. S. Constitution is deeply rooted in the Articles of Confederation. Historian Max Farrand has pointed out that the "surprising thing, especially to one accustomed to condemn the Articles of Confederation, is to see how large a part of the powers vested in Congress were taken from the Articles of Confederation . . . it is not too much to say that the Articles of Confederation were at the basis of the new Constitution."

The writings of James Madison, the Father of the Constitution, corroborate Farrand's remarks. In all of American history, there is no one more qualified as an expert witness to write about the Articles' impact upon the constitution than Madison himself: "If the new Constitution be examined with accuracy and candor, it will be found that the change which it proposes consists much less in the addition of NEW POWERS to the Union, than in the [24] invigoration of its ORIGINAL POWERS. The powers relating to war and peace, armies and fleets, treaties and finance, with the other more considerable powers, are all vested in the existing Congress by the Articles of Confederation. The proposed change does not enlarge thee powers; it only substitutes a more effectual mode of administering them."

Madison's texts fully refute accusations from historians who content that the Constitutional Convention rejected the Articles of Confederation and redesigned a new government from the ground up. Furthermore, even the Preamble to the Constitution itself stated Madison's view, boldly announcing to the world that the Constitution was an extension of an already pre-existing government: "We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union. . ."

The Legal U.S. Birth Certificate

The official 'bottom line' is reached when a major legality arises and an individual (person or nation) must produce proper identification. After the Revolutionary War, during negotiations at the Treaty of Paris, John Adams was challenged by Austrian and Russian mediators to allow separate negotiations between England and each of the thirteen states. Adams responded swiftly. He referred the ministers directly to the Articles of Confederation and the clauses surrendering the independence of the thirteen states as separate sovereignties. Adams then pointed to Articles which expressly delegated the U.S. Congress with the authority to negotiate with foreign nations. This incident established a clear precedent for international legal matters. When the time had come for the U.S. to show its legal ID — its birth certificate — the articles of Confederation and perpetual Union were produced, not the Declaration of Independence!

Ratification is Not Birth

Contrary to the 19th century's popular belief that the Articles of Confederation were not in force until officially and unanimously ratified in 1781, the Confederational government went into effect at the time of the Articles' approval in 1777. Delegates to the Continental Congress had been freely chosen or elected directly as representatives of the people from their respective colonies. This was a case of grass-roots democracy in action. Consequently, the people entrusted their delegates with full legislative powers and specifically instructed them to establish a Union. Article XIII stated that the delegates were direct agents for the states and had given the powers of legal ratification themselves. This means that the act of approving the Articles of Confederation was, by itself, an unofficial ratification.

The Circular Letter from Congress, dated September 8, 1779, sets the record straight about the legal function of the Articles of Confederation after their adoption. Prepared by John Jay, president of the Confederational Congress, the letter informed the states that: "For every purpose essential to the defense of these states in the progress of the present war . . . the States now are as fully, legally, and absolutely confederated as it is possible for them to be."

Distinguished constitutional scholar and eminent historian, Richard B. Morris comments: "This remark has peculiar relevance, because the Articles of Confederation had already lain on the calendar for a good two years and still lacked ratification by one state. Here was the president of Congress, acting on behalf of that body, declaring that such unanimous ratification was not necessary, a position supported in some part by the fact that the Articles were silent on the number of states needed for ratification."

And if that weren't enough evidence to prove a point, James Madison, future Father of the Constitution, responded to President Jay's remarks with his full approval! With strong nationalistic tones, he noted "a sense of common permanent interest, mutual affection . . . and splendor of the union conspiring to form a strong chain of connection, which must forever bind us together."

Several other facts point to a pre-1781 existence of a national government as well:

1) Eleven of the thirteen colonies wrote their state constitutions prior to March 1781 and yet not one of them claimed powers of national sovereignty, i.e. military defense and foreign affairs.

2) On February 6, 1778, less that three months after adoption of the articles, the Confederational government entered into two official treaties with France — a military and a commercial alliance. For centuries, the capacity of a government to enter into relations with other states and exercise its own foreign affairs internationally has been recognized as the add test of national sovereignty. To this day, it still remains a commonly accepted tenet of international law.

3) The Confederational Congress began issuing international passports in 1778, another action that officially confirmed its status in the international community of nations.

4) The pre-existence of the U.S. as a single, sovereign nation was France's primary condition for economic and military aid. French foreign aid was being received by the U.S. already in 1778.

5) Writing in 1779, James Madison stated that the Confederational government had long ago assumed the war debt. This could not have occurred if a national government did not exist until 1781. In that case, the states themselves would have been responsible for the majority of the Revolutionary War debt as it had been prescribed by the Declaration of Independence.

All these factors combined lead to the conclusion that government under the Articles of Confederation was alive and well from the moment of its inception on November 17, 1777.

Although imperfect and weaker than our present Constitution, the Articles of Confederation created a solid, credible government. The primary argument historians offer to discredit the Confederational government is its weak beginning. Boomerang logic, however, turns this contention against its promoters. New-borns are, by definition, inherently weak. Can you envision "proving" that an infant is unborn simply because it is weaker than an adult?

Imagine now, for just one moment, what our continent would be like had the Articles of Confederation not been approved. What is now the continental U.S. might have remained, even to this day, a vast conglomeration of separate countries not unlike Europe. Think about it. The Declaration of Independence is the document that headed America toward a collage of political and economic [25] boundaries. It would have inspired a high level of competition and infighting that might have even paralleled Europe in the first half of this century. The Founding Fathers averted that course after spending one and a half years in and out of intense negotiations to forge a legal agreement acceptable to each of the individual states. That's why November 15, 1777 is the key turning point in U.S. history. It is that moment when all the philosophical eloquence was put into action. It is that moment in history when the Founding Fathers walked their talk. As for the Declaration, historians freely admit it lacked the force of statutory law.

A Key Witness

Our last contemporary witness is John Rogers, a personal consultant to General Washington during the Revolution: "Again, the formation and completion of that social compact among these States, which is usually stiled the Confederation, is another instance of the great things our God has done for us. This is that which gives us a national existence and character . . . By this event, the Thirteen United States . . . became ONE PEOPLE."

Numismatic Breakthrough

Money is the very lifeblood of a society, directly affecting every human transaction between citizens of a nation. It established a legal basis for the existence of a government and also provides an ever-present symbol of a national consciousness. As a consequence, its importance as historical evidence should not be overlooked. Referring back as early as Ancient Rome and the biblical times of Herod the Great, historians have utilized numismatic research as their best evidence in determining the accurate date of inception of a ruler's reign Why shouldn't this time-tested chronological instrument also be employed in historical research for the date of inception of the United States of America? The legal status of numismatic research is beyond reproach, and its mythical-symbolic representation of national consciousness remains unsurpassed.

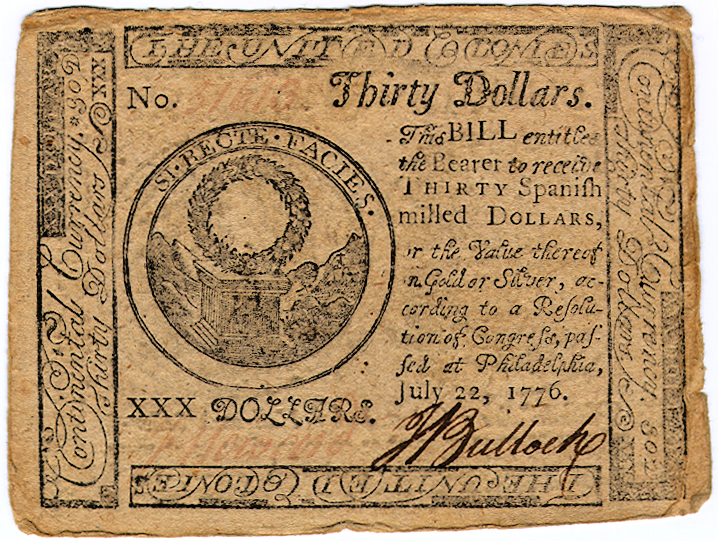

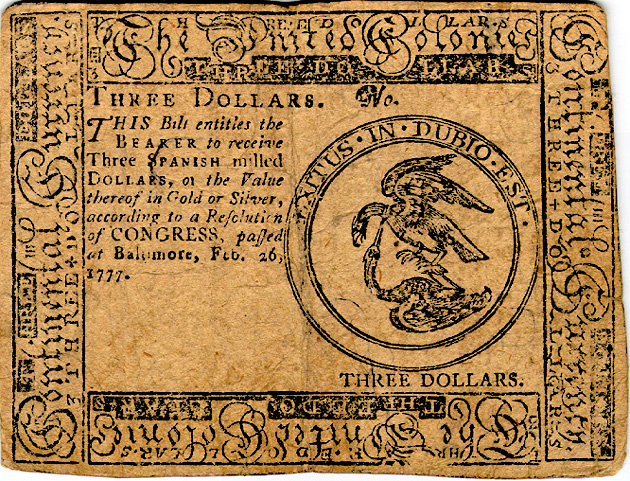

The first emission of Continental Currency was put into circulation in August of 1775. It bore the date of the May 10, 1775 session of the Second Continental Congress. The title, THE UNITED COLONIES, was engraved in fancy script on the top and bottom borders of the various denominational notes. This established a systematic pattern that continued without exception — even after the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776!

The July 22, 1776 resolution of the Continental Congress authorized a new emission of currency. More than two weeks after voting for independence, the same Founding Fathers consciously avoided the title, THE UNITED STATES. One wonders "Did the Founding Fathers absent-mindedly forget to change the engraved cuts due to the hectic pace of business after the Fourth of July?"

Hardly! Instead, they actually took extra time to change the style of fancy script that inscribed THE UNITED COLONIES, reverting back to a style almost identical to that employed for the November 29, 1775 resolution. Then one wonders, "was there some sort of miscommunication between the Congress and the Currency printing office?" Apparently not. The subsequent November 2, 1776 resolution continued usage of the inscription, THE UNITED COLONIES, and so did the February 26, 1777 resolution, and then the May 20, 1777 resolution as well. More than ten months and four resolutions after the Declaration of Independence was approved, the Founding Fathers stubbornly resisted changing the legal name of the colonies.

After the November 15, 1777 founding of our nation at York, [26] Pennsylvania (Yorktown), a dramatic change occurred in our currency. On April 11, 1778, for the first time in America history, the title THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA was engraved on the top and bottom borders. All semblances of the original titles had completely vanished! This was the first currency resolution to be passed by Congress since the founding on November 15, 1777. Because Congress was still located at the site of the nation's founding when the resolution was authorized, this emission was known as the Yorktown issue.

All currency resolutions from April 11, 1778 and after bear THE UNITED STATES title engraving without exception. These include both the resolutions of September 26, 1778 and January 14, 1779. The 1779 resolution added North America to the title, becoming THE UNITED STATES OF NORTH AMERICA.

CONCLUSION: As you can well imagine, there are a lot of philosophical arguments that can be offered to avoid the truth about our nation's birth date. However, one piece of evidence which Declaration proponents cannot avoid is numismatic evidence. It leaves July Fourth advocates, both astrologers and historians, with a lot of explaining to do. If the Founding Fathers truly believed they were founding the United States of America when they declared independence, they would have appropriately removed the old title, THE UNITED COLONIES, and replaced it with THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

The Astrological Psyche

"The eagle typified the sun in its material phase and also the immutable Demiurgic law beneath which all mortal creatures must bend. The eagle was also the hermetic symbol of sulphur and signified the mysterious fire of Scorpio . . . the signature of the Mysteries may still be seen on the Great Seal of the United States of America . . . the American eagle upon the Great Seal is but a conventionalized phoenix . . ."

Manly Palmer Hall

An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic,

Qabbalistic, and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy

The symbols of a nation are direct reflections of its archetypal myth. The more we contemplate this myth, the more we are able to understand the national psyche itself. As a symbol, the Eagle has dominated the American psyche from its earliest years. With its selection for the Great Seal in 1782, the Eagle was officially recognized as the national archetype. Defined in the simplest of terms, one can say that an archetype is "a universal image or idea affecting billions of people over centuries of time."

The landing of a man on the moon was one of the United States' greatest achievements. The Scorpionic symbology of the feat was verified by Neil Armstrong when be announced to the entire world: "The Eagle has landed." A billion people listened to those first words from the moon, words etched in the mind of the human race for future aeons. Across the deep, infinite void of outer space, the word "eagle," the national archetype of the United States of America, had been transmitted to the far corners of the Universe.

The astrological heritage of America is very real. The entire identity of our nation and government is permeated by Scorpio's symbology. As a people, we are in contact with it and reminded of its significance daily. The Eagle's symbol has been minted on billions of coins and engraved on trillions of one dollar hills. The Star-Spangled Banner depicts our nation at war with airborne rockets and "bombs bursting in air," leading to an eventual victory of the forces of light over darkness. Through its words and melody, our national anthem represents the Scorpionic struggle for existence at its fullest, most dramatic expression. In our schools, we still remember the ultimatum voiced by Patrick Henry — "Give me liberty or give me death" — as one of the most fundamental expressions of the national psyche. The final words of Nathan Hale — "I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country" — reinforce that example. National and state elections are the very heart of our democracy and the freedom it bestows, and they occur during Scorpio's annual cycle.

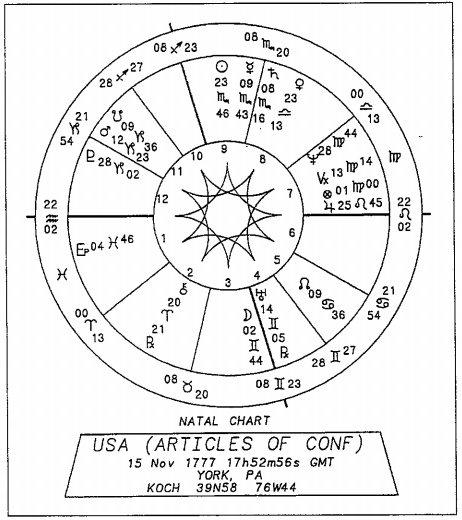

From the historical perspective developed earlier, the United States' date of birth has already been determined as November 15, 1777, however, the exact time of day is not provided in any of the records. Nevertheless, there are sufficient clues. Pages 395 and 401 of the Journals of Congress, Vol. III., point to sometime between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. By turning to rectification procedures to fine tune, 12:46 p.m. LMT surfaced as the indicated time of the Articles of Confederation's approval. (see chart)

Traditional astrology profiles the Scorpio personality as one based on power and self-control. These qualities in turn create a character that is intense, strong-willed, secretive, courageous and passionate. More than any other sign, Scorpio has the potential to destroy and regenerate, to resent or forgive, to rise to spiritual heights or self-destruct. An inner sense of moral truth and self-honesty is the key to unlock the Scorpio personality.

Andrew Shapiro's book, We're Number One (New York, 1992) stands as a clear indictment of the July 4, 1776 Cancer chart. His hard facts provide irrefutable evidence that America's children are the most neglected in the developed world. IN FACT, EVERY CANCERIAN CHARACTER TRAIT TYPICALLY ASSIGNED TO THE UNITED STATES TOTALLY FAILS WHEN COMPARED TO HIS STATISTICAL RESEARCH — WITHOUT EXCEPTION. Those areas in which the Cancerian chart should excel are the very ones which cast it to the bottom of the data heap. Shapiro utilized the most reliable statistical data available from the United Nations, World Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Health Organization, the World Values Survey and similar sources dated from the late 80's through 1991.

Among the nineteen major industrial nations of the world the United States is Number One in homelessness, Number One in children living in poverty, Number One in the murder of children, Number One in infant mortality, Number One in infants born at low birth weight, Number One in not offering paid maternity leave, Number One in abortions, Number One in preschoolers not immunized by vaccination, Number One in single-parent families, and that's just the tip of the iceberg. We're also Number one in:

- percentage of population without health insurance

- death of children younger than five

- death due to breast cancer

- reported rapes

- junk food consumption

The plot thickens as we turn to categories where America finishes last:

- teacher's salaries

- spending on the poor, aged and disabled

- humanitarian aid to developing countries

- paid vacation days (time with family)

Although Cancers are known to hold on to their money, America is last in investing and saving. America doesn't even hold on to things around the house — we're Number One in garbage per capita. Far from being the Cancerian caretakers of the world and the environment, the U.S. is Number One in hazardous waste per capita, Number one in greenhouse gas emissions, acid rain, air pollutants, and forest depletion. If ever a nation existed with four of its seven traditional planets in Cancer, America is NOT it!

Instead, it's a tough cruel Scorpionic world out there. The U.S. is Number One in:

- AIDS

- murder

- gun ownership

- deaths by gun

- murderers still at large

- percentage of population willing to fight for their country

- defense spending

- R&D funds devoted to defense

- military aid to developing countries

- percentage of populations who have been crime victims

- incarceration

- drug offenders per capita

- drunk driving fatalities

- robbers and thieves per capita

- cancer among men

- coronary bypass operations

- divorce

- real national wealth

- unequal wealth distribution

- executive salaries

- inequality of pay

- billionaires

- bankers

- credit cards

- ATM machines

- bank failures and bailouts

- budget deficit

- foreign debt

- Fortune 500 international companies that lose money

- lawyers

- litigation

- nuclear reactors shut down, suspended and canceled

- nuclear reactors in operation

This statistically derived profile of America points to one fact — the United States is a SCORPIOPATH, i.e. a nation trapped within its own obsessions, addicted to secrecy, money, sex, weapons, power, gambling, religion, entertainment, drugs and denial!!