The place was the royal residence of Prince Adam Wisniewski in Rome and the time was a September day in 1894. Members of the Italian court, social personages, patrons and performers of the arts had gathered to witness a musical seance. Seated at the piano was the medium, a tall, slender middle-aged man with a trim dyed moustache and large brown eyes. On his head was a wig of dark wavy hair and his cheeks were slightly rouged. The guests were placed in a circle around the piano and the room was darkened. As the pianist, his huge hands covering an octave and a half, struck the first chords, tiny lights flickered in every corner of the room. The great composers of past centuries had arrived, some to listen, others to perform from the beyond their latest compositions through the dexterous fingers of the medium. Thalbery was first with a rippling fantasia, then he was joined by Liszt in a rhapsody for four hands. "Notwithstanding this extraordinary complex technique," wrote the Prince in Vessillo Spiritista, "the harmony was admirable, such as no one present had ever known paralleled even by Liszt himself, whom I personally knew and in whom passion and delicacy were united. In the circle were musicians who, like myself, had heard the greatest pianists in Europe, but we can say that we never heard such truly supernatural execution."

A globe of light and three raps on the Prince's knee announced the appearances of Chopin and George Sand, respectively. Then Chopin's spirit, with the expressive tones that distinguish his compositions, played first a fantasia followed by haunting and exquisite melodies "with a pianissimo of diminishing notes and tones full of despair -- a prayer to God for Poland."

The somber mood was dispelled by Mozart who played with the agility and lightness of a sylph, the genius of his unique and melodious style displayed by notes that danced to an airy climax above a Lydian measured undertone.

"But the most marvelous incident of the evening was the presentation of the spirit of Berlioz by his two chaperones, Liszt and Thalberg," the Prince reported. "That was the first time Berlioz had played through Jesse Shepard. He began by saying that the piano was toned too low for his music (Shepard is also clairvoyant and clairaudient) and he tuned it a tone higher himself. For ten minutes we heard the spirits working with the piano, which was closed. At the first sound we observed that the instrument was about two notes higher.

"Then Berlioz played sweet, ideal music. It seemed as if we heard the little bells of a country church; as if we saw and heard a marriage procession . . . entering the edifice; then a music which imitated to perfection the sound of the organ and continued piano, pianissimo and morendo, as if indicating that the marriage was celebrated . . . This piece finished, Berlioz, with the aid of several other spirits, restored the instrument to its first tuning and began playing on its ordinary tone while the lid was still shut."

Jesse Shepard could speak English and French only, but after the musical seance he entered a trance state and the spirits spoke through him in other languages. Prince Wisniewski said that Goethe came and recited passages in German, while other spirits spoke in Hebrew and Arabic. "After the seance," the article concluded, "Mr. Shepard was much exhausted and had to retire to rest."

As the late Dr. Nandor Fodor wrote in his book Between Two Worlds, "No musical party by the Mad Hatter could sound more preposterous than this account. It leaves breathless the most ardent spiritualists." Did Prince Wisniewski make an accurate report or was he guilty of exaggeration? Whatever the source of his inspiration, Shepard was a master pianist whose improvisations left his listeners dumbfounded. Varied in style, emotionally powerful, his music sometimes had a delicate lilting beauty and at other times it was haunting, primitive. His renditions roamed the world and the centuries. With processions of chords, he evoked the antiquity of Egypt, the mystery of India, the agelessness of china, and the sophistication of the West.

John Lane, the English publisher, was a guest one evening at a Shepard musicale when the performer improvised on the sinking of the Titanic. The treatment was so stupendous, so overwhelming, Lane said it caused him to postpone his departure for America for a fortnight, although he had arranged to sail the very next day. Edwin Bjorkman, writing in Harper's Weekly, described a Shepard concert: "Something more than sound issued from that piano: it was a mood, uncanny yet pleasing, exalting, luring. He seemed to keep notes suspended in the air for minutes. How and then he would make a shining vessel out of such a chord, and then he would begin to drip little drops of melody into it, until the Grail seemed to rise before your vision, luminous with blood-red rubies . . ..Then the music swelled and became strangely urgent -- I left there was an image that wanted to break through -- a consciousness of some mighty presence."

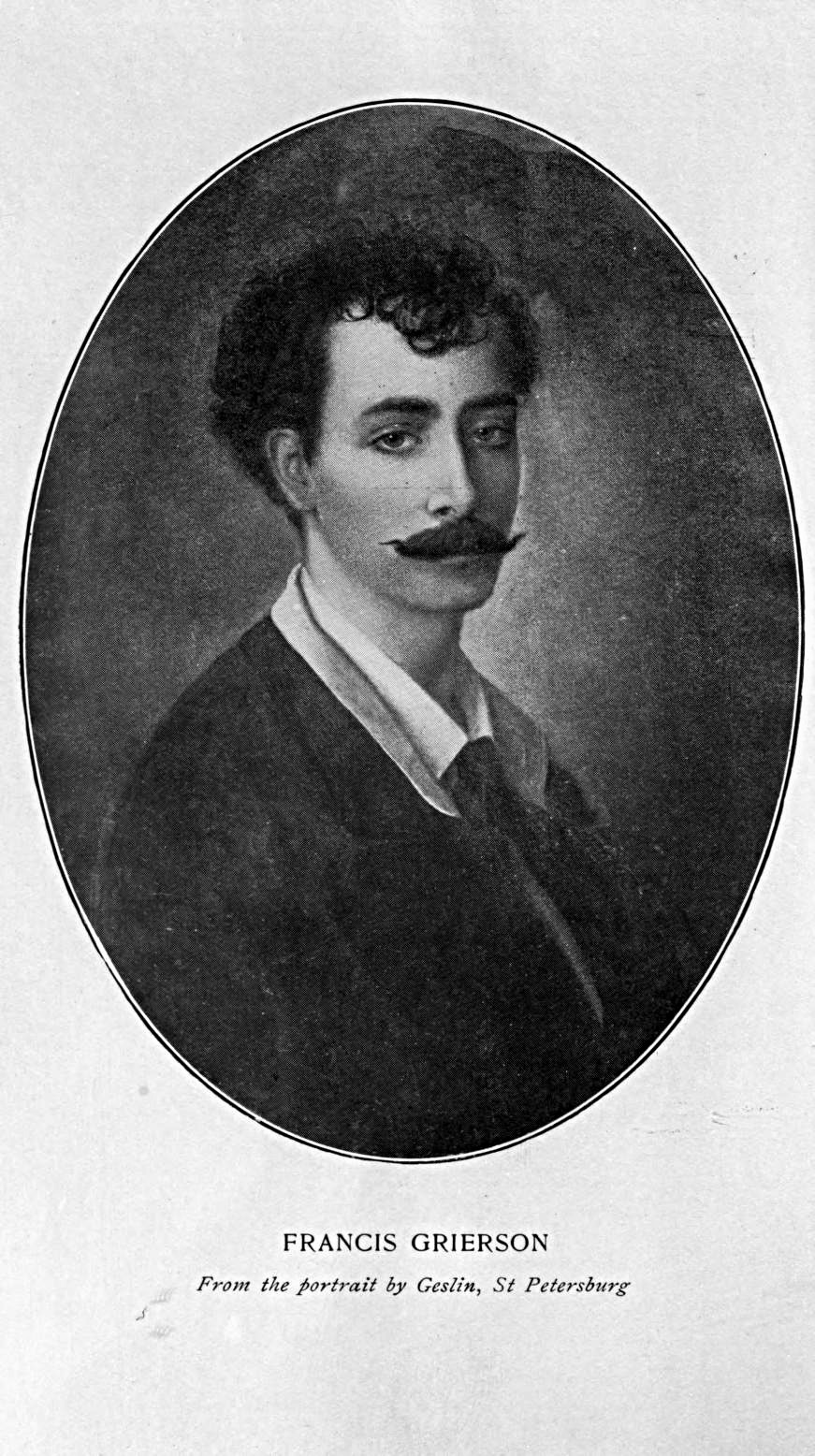

Prof. Harold P. Simonson, author or the only book-length biography of Shepard, writes that to Shepard "music was the medium to supra-conscious experience. An intransigent foe of positivism, relativism and determinism -- of all ‘isms' denying the power of the invisible and the reality of absolute spirit -- (he) by means of musical seances, sought to lead others to transcendental perception." (Francis Grierson, by Harold P. Simonson, Twayne Publishers, Inc., NY, 1966.)

Unlike Rosemary Brown, the contemporary English housewife who has produced hundreds of astonishing and gifted compositions said to have dictated by Liszt, Chopin, Schubert, Beethoven and other musical geniuses of yesteryear, Shepard's music was never committed to paper. He believed that to do so would nullify the rationale of his gift. Some of his improvisations had titles and basic tonal structures, but his renditions were never exactly the same.

Born in England in 1848, Jesse Francis Shepard was brought to the United States as an [37] infant by his parents. The family settled on the Illinois prairie, in Sangamon County, in the heart of the Lincoln country. For a time his log home was a station on the Underground Railway, and at the age of ten he listened to the final Lincoln-Douglas debate at Alton. Three years later, as the Civil War got underway, he was a page to Gen. John C. Fremont in St. Louis.

Later the family moved to Niagara Falls and then Chicago. Shepard, in an biographical article in The Medium, a London spiritualist publication, said that his first psychic abilities of clairvoyance and psychometry appeared when he was 19. Meanwhile he was taking piano lessens and developing his skill in a normal manner. In fact, for a time, his sister Letitia played better than he did. When and where did the baptism of transcendental proficiency take place?

The mystery of this musical medium is presented in Twentieth Century Authors: "With only two years of formal musical training, Shepard exhibited an extraordinary talent at the piano. At barely 21, he set out for Paris, with scarcely enough money to buy his own passage, and almost overnight became a sensation." Without a knowledge of French, letters of introduction, companions or a reputation as a musician, he received immediate acclaim as piano improvisator par excellence. Within a month he was a welcome guest at the Parisian salons where he entertained those distinguished in titles, society and the arts. In addition to his instrumental endowment, Shepard was blessed with a remarkable voice. He sang in Saint-Eustache and the basilica of Montmartre by special invitation, and was chosen by composer Leon Gasinelle to sing the leading parts in his Mass written for the fete of the Annunciation and performed with orchestra and chorus in the Cathedral of Notre Dame. "With your gifts you will find all doors open before you," Alexandre Dumas the Elder told Shepard at a reception.

Now the darling of French nobility, Shepard received so many social invitations that he sought the advice of friends in dealing with them. But in time the Franco-Prussian War brought his happy stay in the City of Lights to an end. He went to London where he stayed at the home of Viscountess Combermere. He continued his recitals for the distinguished and socially elite and also advertised that his psychic services were available -- "clairvoyant, prophetic, psychometric sittings, diagnosis of disease, and discovery of mediumistic faculties," with the added note that "music manifestations are not given at the same sitting."

After eight months in London he spent a delightful summer in the German resort city of Baden-Baden where his circle of aristocratic friends included the King and Queen of Prussia. In October, with no knowledge of the Russian language and with only enough money to pay expenses for one week, he moved on to St. Petersburg. After spending the week in a hotel room reading the works of Lord Byron, he took his limitless optimism and a letter of introduction to Madame and Monsieur Hardy. owners of the opulent Restaurant Dusseau. They took him in, and while the fierce Russian winter raged and howled he moved among the high and mighty, his days "crammed with pleasure and amusements of all sorts." Princess Abamelik introduced him to General Jourafsky, the noted Russian mystic who discussed with him the proper conduct of seances. Shepard climaxed his first visit in the spring by performing before Czar Alexander II, then returned to London.

In the autumn of 1874 he returned to the United States. Within a month he was in Chittenden, Vt., attending the seances of the Eddy brothers in their farmhouse. He spent ten days there with Madame Blavatsky and Col. Henry Steel Olcott, later the co-founders of Theosophy, as crowds of the curious came and went. According to Olcott, in his book "Old Diary Leaves", Shepard not only gave "mediumistic musical performances," but entered into the spirit of things by going into trance and singing Russian songs "under the control of Grisi and Lablache."

Back in New York Shepard continued to visit Madame Blavatsky, but a personality conflict finally developed. She told Olcott Shepard was a charlatan and accused him of having paid a music-master to teach him the Russian songs he sung in the Eddy farmhouse. But theosophical teachings were another matter, and years later he lectured on the doctrine. During the next 12 years Shepard roamed the world living by his wits and talents in northern California, Europe and a year in Australia. In Chicago he held a series of seances in the home of another medium, and according to the daughter of Hudson Tuttle, "strange and unaccountable phenomena nightly occurred." Tuttle is the noted author of classical books on spiritualism. Shepard, the daughter reported, said he was controlled by a bank of Egyptian spirits, the leader of whom had lived on the earth when the pyramids were young.

The medium's most amazing performance was simultaneously singing in two voices, in bass and soprano, his control singing in one voice and the Egyptian in the other, while another spirit accompanied on the harp. "Between the musical pieces," she added, "Mr. Shepard, ‘under influence,' gave tests, describing spirit friends, etc." Throughout his career Shepard's dual-tone singing left his listeners in states of bewildered shock. And it was in Chicago that he met Lawrence W. Tonner, his self-effacing modest secretary, man Friday and dedicated admirer, who would be his companion the rest of his life. A few months later they came to San Diego, Calif. Here Shepard would build his magnificent Victorian mansion, the Villa Montezuma, and enter a new profession. He had reached life's mid-point, a Midwest farm boy who had become a globe-trotter over three continents; a cosmopolite honored in the salons and palaces of society and royalty. Now would come a time for inner searching, a change in goals, a personal renaissance.

Designated a historical landmark, the Villa Montezuma is currently being restored by the San Diego Historical Society, the San Diego Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, and the Save Our Heritage Organization. Upon completion of the work it will be furnished with period furniture and open to the public. Its exterior is somewhat weathered, but the main floor of the interior with its polished redwood walls, ornate tiled fireplaces, silvery lincrusta walton ceilings and cathedral glass transoms is almost the same as when the house was built in 1887. There are ebony panels inlaid with bas-relief figures of ivory and mother-of-pearl. A mantel in the design of a medieval castle tower is made of walnut shingles and imported English tiles. It is the colored art glass windows that Shepard had made to order that is the home's outstanding decorative feature. On the long east wall of the music room is a huge window depicting the Greek poetess Sappho attended by two cupids. At the north end of the room are circular windows containing portrait heads of Mozart and Beethoven in art glass, while on the south wall are similar windows with portraits of Rubens and Raphael. In the drawing room are the heads of Shakespeare, Goethe and Corneille. Other art windows included allegorical representations of the Orient and Occident (the face of the figure representing the Orient a portrait of Shepard himself), the four seasons, at St. Cecilia playing the organ.

When Shepard lived in the house, the floors were covered with heavy Persian and Turkish rugs with a large polar bear skin in the music room. An elaborate Oriental candelabrum hung from the ceiling, and throughout all the rooms were life-sized busts, exotic plants and polished candelabra. The second floor, since remodeled into rooms, was originally an art gallery and museum displaying along with sculpture and paintings, memorabilia and gifts Shepard had received from royalty, titled patrons and others during his tours. A Spanish cedar stairway led up to a third floor tower room beneath a Moorish roof. This was Shepard's study.

Private seances were held in the music room. [38] So beatific, so unearthly was his music that contemporary accounts call it "simply indescribable." There were listeners who said they heard drums, tambourines and trumpets accompanying the piano with voices issuing from the trumpets. Other guests claimed they heard choirs of voices led by Shepard's own singing, now soaring to the heights in melodious soprano, then dropping down to an euphonious bass.

Two changes occurred in Shepard's life during his San Diego period, one temporary, the other permanent. There was a crisis in his spiritual and religious thinking. Although he continued his musicales and was associated with a group of wealthy local spiritualists who had contributed heavily to the cost of his villa, he seemingly tried to break away from spiritualism. He attacked what he called "phenomenal spiritualism" which led to a bitter counter-attack by Hudson Tuttle in an article in the Religio-Philosophical Journal. His upheaval was climaxed by his becoming a member of the Roman Catholic Church. The permanent change was his decision to embark on a literary career with music taking second place. This career began with the writing of essays for The Golden Era, a West Coast journal that published much of the early work of Mark Twain, Bret Harte and Shepard's friend, the poet Joaquin Miller. Most of them were written in the tower room where in later years it is said a butler hung himself.

Late in 1888 Shepard and Tonner went to Paris to arrange for the publication of his first two books, both containing some of the earlier Golden Era essays. They returned the following September. Shepard decided that to achieve literary success he should move permanently to Europe. He needed money. On Dec. 17, 1889, he completed the sale of the Villa Montezuma and all its furnishings to David D. Dare, a bank executive, and that night gave his farewell concert before a large audience at the Unitarian Church.

In a biographical sketch Tonner wrote: "Certain rich townspeople gave the land and some of the money to build the villa, the idea being to attract attention to the town (which it certainly did) . . . When the boom died out in San Diego in 1889 we had to sell for what we could get. We gave half the proceeds to those who had supplied the money, which they considered quite generous, for it was not thought necessary to return any; and the following year we went to Europe."

Their arrival in Paris marked the beginning of a twenty-three year residence abroad. Shepard resumed his European tours and published reports revealed that he was still the musical medium. In Austria he played at a reunion of three royal houses as the guest of the duchess of Cumberland. The Queen of Denmark said that the piano playing was so marvelous that it seemed four hands were engaged instead of two. Again he was welcomed in royal courts and cosmopolitan salons.

Unless he knew his listeners were sympathetic, Shepard did not refer to psychic inspiration. Few would believe such claims, and those who did were regarded by others with suspicion. According to Dr. Fodor, the penalty for belief could be great. Henry Kiddle, Superintendent of Schools of New York, was forced to resign when he publicly said he believed in Shepard's spirits. The school official said he heard Shepard play a magnificent impromptu symphony under the control of Mozart, give philosophical dissertations under the influence of Aristotle, and speak in six different languages while in trance.

During his European years Shepard was writing essays, articles and books on art, philosophy, human nature, biographical sketches and his own experiences. With the publication of his book Modern Mysticism in 1899, he took one of his middle names and his mother's maiden name "lest his literary efforts be regarded as mere diversions. Thus, during the last 28 years of his life the former Jesse Shepard became Francis Grierson.

Included among his published books were The Celtic Temperament (adopted as a textbook by Japanese universities), Parisian Portraits, The Humour of the Underman, and Abraham Lincoln, the Practical Mystic. In 1911 his Invincible Alliance foresaw World War I.

He won the admiration and praise of the leading critics and literary greats of his day. Maurice Maeterlinck found his writings mystical, romantic and profound. The Westminster Review noted his "rare intuition and a profound knowledge both of art and human nature." Grierson's greatest work was The Valley of Shadows, the story of his boyhood on the prairies of Illinois, in Lincoln country, at the time of the spiritual awakening as the Civil War approached. It presents a poetic and vivid picture of a bygone time, and was used by Carl Sandberg as an information source in writing his Abraham Lincoln, the Prairie Years. When the fifth edition appeared in 1948, Bernard DeVoto called it an American classic. Edmund Wilson, reviewing it in The New Yorker, said it fills a "niche which no other book quite fills." This edition came 39 years after if was first published.

Grierson and Tonner returned to the United States in 1913. He continued his writing and piano recitals. For a time he was in Toronto giving lecture on theosophy. He made many friends. Judge Ben Lindsey introduced him to Henry Ford and he was invited to membership in the Chevy Chase Club. He discussed the fourth dimension and occult theories with Claude Bragdon. His literary friends included Edwin Markham, Sara Teasdale, Mark Van Doren, William James and Edwin Arlington Robinson.

In 1920 he settled in Los Angeles and a year later published his final book at his own expense. It was titled Psycho-Phone Messages, and its 82 pages contained communications allegedly received through a phone-like device from illustrious but deceased persons. Abraham Lincoln predicted the failure of the League of Nations; Henry Ward Beecher assailed the sins of the Jazz Age; and Elizabeth Cady Stanton preached Women's Lib. Other messages, warnings and diatribes came from General Grant, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Daniel Webster, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and other great personalities of yesteryear. Grierson's final years were sad ones. The public was no longer interested in his music. Despite the efforts of admiring fellow authors, publishers failed to express sufficient interest in his manuscripts. Occasionally he gave a lecture or lessons in poise and practical psychology. Tonner taught French and for a time was a partner in a small dry cleaning establishment. Despite the recommendations of Mary Austin, an anthology of poetry Grierson had compiled and edited could not be sold. Eventually all sources of income failed and the pair were destitute.

Zona Gale, the Pulitzer Prize winning novelist, was staying at the famed Mission Inn in Riverside, Cal., where Grierson sometimes gave concerts. He visited her at her request. When she arrived back home at Portage, Wis., she wrote friends in Los Angeles and encouraged them to arrange a benefit dinner to honor Grierson and to raise money for him. In the meantime he pawned the last of his valuable possessions, a gold watch given him by King Edward VII of England.

The benefit was held the evening of May 29, 1927. Following the dinner Grierson entertained with what Tonner called "marvelous instantaneous compositions on the piano." Finally the pianist told the thirty guests that his final number would be his Grand Egyptian March. It was a moving rendition, haunting and mystical, with mighty chords alternating with soft melody that invoked thoughts of dark antiquity, of temples, the ever-flowing Nile, of gods dethroned and empires of the past.

When he finished he sat perfectly still as he often did as he rested, his head slightly bent forward, his fingers on the keys. There was applause but he failed to acknowledge it. Long seconds passed. A grim suspicion gripped Tonner. He walked over and touched his companion of over four decades. It was true! Dramatically, yet quietly, surrounded by friends, he had entered the realm of his visions and found peace.

Selected Bibliography of Francis Grierson

- Grierson, Francis. Modern Mysticism and Other Essays. London: George Allen, 1899. Print. [Digital, 1910 ed.: <https://archive.org/details/modernmysticismo00grie>]

- Grierson, Francis. The Celtic Temperament and Other Essays. London: George Allen, 1901. Print. [Digital, 1913 ed.: <https://archive.org/details/celtictemperamen00grieiala>]

- Grierson, Francis. The Valley of Shadows. London: A. Constable, 1909. Print. [Digital: <https://archive.org/details/valleyofshadows00grie>]

- Grierson, Francis. Parisian Portraits. London: s.n., 1911. Print. [Digital, 1913 ed.: <https://archive.org/details/parisianportrai00griegoog>]

- Grierson, Francis. The Humour of the Underman: And Other Essays. London: Stephen Swift, 1911. Print. [Digital: <https://archive.org/details/humourofunderman00grieuoft>]

- Grierson, Francis. Abraham Lincoln: the Practical Mystic. New York: John Lane, 1918. Print. [Digital: <https://archive.org/details/abrahamlincolnp1761grie>]

- Grierson, Francis. The Invincible Alliance: And Other Essays, Political, Social, and Literary. New York: John Lane, 1913. Print. [Digital: <https://archive.org/details/invincibleallian00grieuoft>]

- Grierson, Francis. Psycho-Phone Messages. Los Angeles, Calif: Austin Publishing Company, 1921. Print. [Digital: <https://archive.org/details/psychophonemessa00grie>]

References

- Fodor, Nandor. Between Two Worlds: Amazing True Case-Histories of the Occult, the Mysterious, the Marvelous and the Supernatural. West Nyack, NY: Parker, 1964. Print.

- Simonson, Harold P. Francis Grierson: a Biographical and Critical Study. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1966. Print.

- Olcott, Henry S. Old Diary Leaves: The True Story of the Theosophical Society. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1895-. Print. [This is a multi-volume series, which has undergone many re-editions through the years. The complete series in digital format: <http://blavatskyarchives.com/theosophypdfs/early_theosophical_publications_authors.htm#O>; in print, 1974 ed., 6 vols.

- Sandburg, Carl. Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1919. Print. [2002 ed., including "The Prairie Years" and "The War Years": <>]